Page 198 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 198

ARAMAEANS AND PHOENICIANS IN SYRIA

of the second millennium b.c. The Assyrian plan came into being long before Assyria

became independent. It occurs at Tell Asmar (Figure 19), and was probably basic to the

arrai lgcmcnts at Mari. At that time, however, there existed in the palace of Yarimlim of

Alalakh (Figure 62) a local north Syrian ancestor of the bit-hilani unrelated to the Meso

potamian palaces.

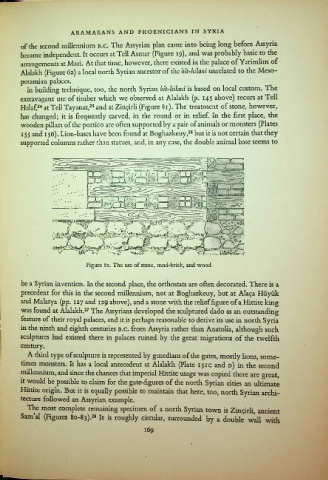

In building technique, too, the north Syrian bit-hilani is based on local custom. The

extravagant use of timber which we observed at Alalakh (p. 145 above) recurs at Tell

Halaf,24 at Tell Tayanat,25 and at Zii^irli (Figure 81). The treatment of stone, however,

has changed; it is frequently carved, in the round or in relief. In the first place, the

wooden pillars of the portico arc often supported by a pair of animals or monsters (Plates

155 and 156). Lion-bases have been found at Boghazkeuy,26 but it is not certain that they

supported columns rather than statues, and, in any case, the double animal base seems to

jams

im

mm ■ ■Jl

EMI m ikjisiii

:

u

Figure 81. The use of stone, mud-brick, and wood

be a Syrian invention. In the second place, the orthostats are often decorated. There is a

precedent for this in the second millennium, not at Boghazkeuy, but at Ala$a Hiiyiik

and Malatya (pp. 127 and 129 above), and a stone with the relief figure of a Hittite king

was found at Alalakh.27 The Assyrians developed the sculptured dado as an outstanding

feature of their royal palaces, and it is perhaps reasonable to derive its use in north Syria

in the ninth and eighth centuries b.c. from Assyria rather than Anatolia, although such

sculptures had existed there in palaces ruined by die great migrations of the twelfth

century.

A third type of sculpture is represented by guardians of the gates, mostly lions, some-

times monsters. It has a local antecedent at Alalakh (Plate 151c and d) in the second

millennium, and since the chances that imperial Hittite usage was copied there are great,

it would be possible to claim for the gate-figures of the north Syrian cities an ultimate

Hittite origin. But it is equally possible to maintain that here, too, north Syrian archi

tecture followed an Assyrian example.

The most complete remaining specimen of a north Syrian town is Zin^irli, ancient

Sandal (Figures 80-83).28 It is roughly circular, surrounded by a double wall with

169