Page 32 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 32

THE PROTOLITERATE PERIOD

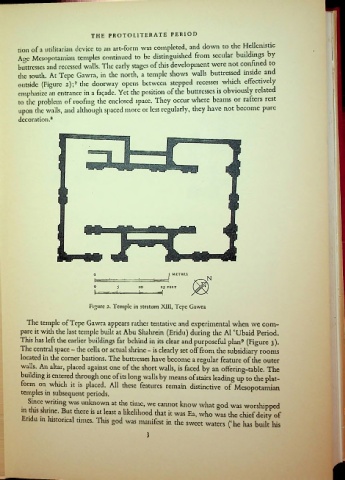

tion of a utilitarian device to an art-form was completed, and down to the Hellenistic

Age Mesopotamian temples continued to be distinguished from secular buildings y

buttresses and recessed walls. The early stages of this development were not confined to

the south. At Tepe Gawra, in the north, a temple shows walls buttressed inside and

outside (Figure 2);7 the doorway opens between stepped recesses which effectively

emphasize an entrance in a facade. Yet the position of the buttresses is obviously related

to the problem of roofing the enclosed space. They occur where beams or rafters rest

upon the walls, and although spaced more or less regularly, they have not become pure

decoration.8

5 METRES

10 15 FEET

*

Figure 2. Temple in stratum XIII, Tepe Gawra

The temple of Tepe Gawra appears rather tentative and experimental when we corn-

pare it with the last temple built at Abu Shahrein (Eridu) during the Al ‘Ubaid Period.

This has left the earlier buildings far behind in its clear and purposeful plan9 (Figure 3).

The central space — the cella or actual shrine — is clearly set off from the subsidiary rooms

located in die corner bastions. The buttresses have become a regular feature of the outer

walls. An altar, placed against one of the short walls, is faced by an offering-table. The

building is entered dirough one of its long walls by means of stairs leading up to die plat-

form on which it is placed. All these features remain distinctive of Mesopotamian

temples in subsequent periods.

Since writing was unknown at die time, we cannot know what god was worshipped

in this shrine. But there is at least a likelihood that it was Ea, who was the chief deity of

n u in historical times. This god was manifest in the sweet waters (‘he has built his

3

i