Page 74 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 74

THE AKKADIAN PERIOD

combatants: hero and bull-man as victors, lion and bull or buffalo as victims. The

scheme of the continuous frieze is, therefore, impoverished by the reduction in the

number and variety of its figures, and by their isolation. But in Akkadian times this

scheme of composition became uncongenial. It was replaced by a static, antithetical,

heraldic composition with an inscribed panel as its central feature.

The Early Dynastic seal-cutters had never solved the problem of how an inscription

could be integrated with their figures. Originally they did not set it apart (Plate 39A)

and it looked like an awkward space-filler. Later (Plate 40B) it was framed below but

left open at the sides; the problem it presented was evaded. But the Akkadians faced it

squarely and solved it by making the inscription the very centre of their compositions.

It was flanked by pairs of combatants, in the manner of heraldic supporters (Plate 45°) •

These seals reveal the polarity of Mesopotamian art in a novel form. While the figures

are rendered with all the concrete details of their physical reality, they are presented in a

purely ornamental arrangement. Plate 45D offers actually a variant of the usual scheme;

the hero does not destroy the buffaloes but waters them from a spherical vessel which is

a common feature of Mesopotamian imagery.15 It stands for the source of all water and

hence for the origin of life. The significance of the buffaloes remains obscure.

Unusual subjects are much more frequent in the Akkadian Period than at any other

time. The frieze of combatants had been developed to its rich variety because of its de

corative potentialities which the Early Dynastic seal-cutters prized. The turn towards the

concrete which marks the Akkadian style led, necessarily, away from the frieze, and a

larger proportion of seals showed narrative scenes, definite events, either in the world of

the gods or in that of men. Such subjects had been relatively rare in Early Dynastic times,

but when we happen to know an earlier version of a subject popular in Akkadian times,

the difference in treatment is revealing. The sun-god in his boat may serve as an example.

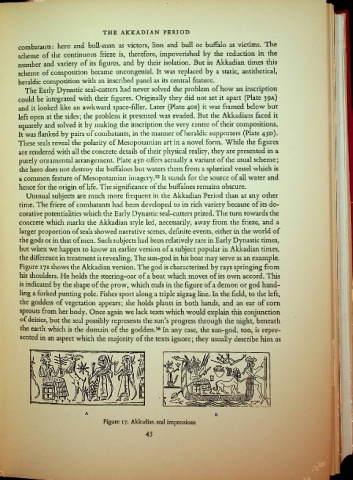

Figure 17B shows the Akkadian version. The god is characterized by rays springing from

his shoulders. He holds the steering-oar of a boat which moves of its own accord. This

is indicated by the shape of the prow, which ends in the figure of a demon or god hand

ling a forked punting pole. Fishes sport along a triple zigzag line. In the field, to the left,

the goddess of vegetation appears; she holds plants in both hands, and an ear of com

sprouts from her body. Once again we lack texts which would explain this conjunction

of deities, but the seal possibly represents the sun’s progress through the night, beneath

the earth which is the domain of the goddess.16 In any case, the sun-god, too, is repre

sented in an aspect which the majority of the texts ignore; they usually describe him as

Figure 17. Akkadian seal impressions

45