Page 19 - 2021 March 16th Japanese and Korean Art, Christie's New York City

P. 19

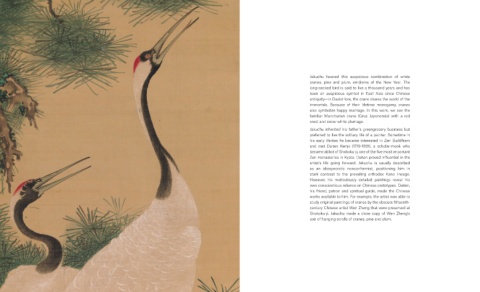

Jakuchu favored this auspicious combination of white

cranes, pine and plum, emblems of the New Year. The

long-necked bird is said to live a thousand years and has

been an auspicious symbol in East Asia since Chinese

antiquity—in Daoist lore, the crane shares the world of the

immortals. Because of their lifetime monogamy, cranes

also symbolize happy marriage. In this work, we see the

familiar Manchurian crane (Grus Japonensis) with a red

crest and snow-white plumage.

Jakuchu inherited his father’s greengrocery business but

preferred to live the solitary life of a painter. Sometime in

his early thirties he became interested in Zen Buddhism

and met Daiten Kenjo (1719-1801), a scholar-monk who

became abbot of Shokoku-ji, one of the five most important

Zen monasteries in Kyoto. Daiten proved influential in the

artist’s life going forward. Jakuchu is usually described

as an idiosyncratic nonconformist, positioning him in

stark contrast to the prevailing orthodox Kano lineage.

However, his meticulously detailed paintings reveal his

own conscientious reliance on Chinese prototypes. Daiten,

his friend, patron and spiritual guide, made the Chinese

works available to him. For example, the artist was able to

study original paintings of cranes by the obscure fifteenth-

century Chinese artist Wen Zheng that were preserved at

Shokoku-ji. Jakuchu made a close copy of Wen Zheng’s

pair of hanging scrolls of cranes, pine and plum.