Page 12 - LDC FlipBook demo

P. 12

It was not until late summer, however, that the railroad companies began removing the cinder and old crosstie fill and repacking it.

By fall, work had started on raising the level of the fill by three to five feet from Hardentown for a mile and a half. Authorities still believed that the portion of the levee that held back the Great Miami was more important than that along the Ohio River itself, and planned for that area to be higher than the portion along the Ohio.

As work began, there were available funds in the amount of $10,000.

By November of 1913, 12 men were at work filling and grading as they widened the base of the levee above Elm Street from 74 feet to about 139. It was widely believed that the amount of clay being placed in that area would make the embankment “perfectly safe.”

At about the same time, a contract was awarded to R.H. Blackmore to place a six-inch concrete facing on the levee near the Mitchell brickyard on High Street.

Council had begun discussions about raising the

height of the levee along the Ohio to 70 feet by adding more fill. By 1918, the levee would protect against a 68-foot flood.

The 1918 ice jam downriver caused serious flooding upstream, and the Ohio began inching upward to 60 feet and more.

Mayor John C. McCullough at first was encouraging,

but as the river continued to rise, he recommended that residents prepare for the worst.

Families began moving furniture to the second and third stories of their homes or to friends’ homes in Greendale.

The river reached 65 feet 4 inches before the ice jam downriver at Patriot broke loose, and by the next morning had fallen to 51 feet.

The levee proved its worth several times over the next fifteen years, especially in 1933, when the Ohio rose to 64 feet.

The heavy rains started in March and continued for several days.

Soon the Aurora Road was cut off by floodwaters, and train service was halted.

Hardentown was submerged and homes outside the levee were inundated, but the levee held.

There were no leaks or slips, but large supplies of sandbags were placed at the ready. They weren’t needed.

At one point, water began backing up through the sewers due to an automatic trap failure, and it took the work of divers to set it right before much harm was done.

The levee was patrolled day and night. Members of the American Legion and Business Men’s Club were pressed into service as watchmen.

A few families left their homes, but most businesses remained open.

Although most residents had confidence in their levee, in 1936, when high water once again seemed probable, a formal organization was set up with the Legion

and Business Men’s Club to patrol the levee, and to volunteer for any other emergency in which they might be needed.

The levee held, and once again Lawrenceburg escaped flooding.

Opposite, clockwise from top left: The levee collapsed at the west end

of Center Street. Hugh waves crashed through every property and caused whiskey barrels to be cast into the raging waters. Seagram Distillery vats and properties were inundated. The floodwaters remained in the city two weeks. The photograph of St. Lawrence Church (foreground) and Lawrenceburg High School (background) against underwater homes and rooftops, records some of the historic damage.

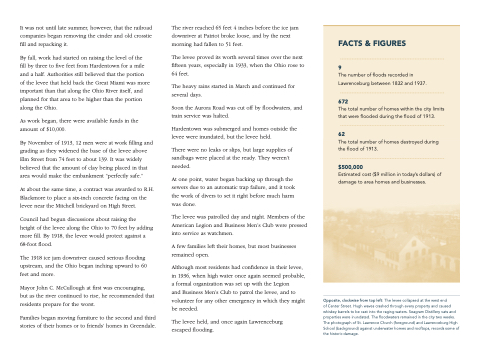

FACTS & FIGURES 9

The number of floods recorded in Lawrenceburg between 1832 and 1937.

672

The total number of homes within the city limits that were flooded during the flood of 1913.

62

The total number of homes destroyed during the flood of 1913.

$500,000

Estimated cost ($9 million in today’s dollars) of damage to area homes and businesses.