Page 14 - LDC FlipBook demo

P. 14

The monthly rainfall at Cincinnati totaled 13.68 inches, a record for January that stands until this day. It was almost four times the normal for the month.

On Thursday, January 21, 1937, Mayor Arthur G. Ritzmann called an emergency meeting of city council. The Ohio River was rising at four inches an hour and by noon it had reached 66 feet.

An exodus that had begun as a trickle during the morning became general during the afternoon, and streets were clogged with trucks and wagons as residents attempted to move their belongings to high ground.

Old Quaker Distillery supplied two trucks and drivers and Dewey Volk, who owned an independent trucking company, volunteered all of his trucks and drivers.

Industrialist Victor O’Shaughnessy was pressed into service once again, and appointed to head up an emergency committee. He immediately called a meeting at the firehouse on Third Street (now Eads Parkway). The area was believed to be absolutely above any possible flood level.

A list of members of the emergency committee reads like a “Who’s Who” of prominent residents of that time.

In addition to O’Shaughnessy, there were Frank Hutchinson of Lawrenceburg Roller Mills; Robert Nanz of Old Quaker Distillery; W.H. Reed of the Joseph E. Seagram Distillery; Carl Stauss, head of the American Legion, E. A. O’Shaughnessy, E.G. Harry, R.V. Achatz, E.G. Bielby, John Stahl, C.A. Lowe, Peter Reagan, Elkannah Barrott, Art Lommel, Rev. J.A. Petit,

Morris McManaman, E.P. Hayes, Bernard McCann, J.W. Riddle, Col. Joe Williams, Dr. G.F. Smith, Dr. E. Libbert, O.M. Keller, Al Spanagel, L.J. Seitz, Wade Fleming and Dr. G.M. Terrill.

They were doctors, dentists, merchants, bankers, educators, restaurant owners, pharmacists, hotelkeepers, bankers, and a wide cross section of Lawrenceburg residents.

Volunteers had begun patrolling the levee while it was still daylight. But by 9:30 p.m., water began coming over the “levee” at Hardentown, and an hour later was coming under the railroad.

Three hundred local men and Civilian Conservation Corps participants were involved in placing sandbags at danger points, but the river was rising so fast that it outpaced even their best efforts.

By 12:30 a.m. January 22, it was obvious to everyone that the situation was hopeless and the fire bells began to toll, which was a warning to residents.

Eventually, the levee gave way completely at the west end of Center Street, and a 25-foot high wave plowed through the opening, sweeping houses and outbuildings in its path.

A total of 32 homes on Center and Maple Streets were destroyed, some tumbling their way to destruction, or they were crushed by collisions with obstacles.

At the end of Walnut Street, George Powell, 58, was attempting to walk from his home on Tate Street to Newtown and safety. As he passed St. Lawrence Church he noticed priests preparing to leave their building, and shouted at them to stay inside.

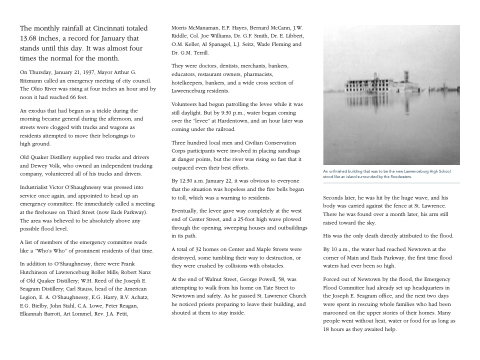

An unfinished building that was to be the new Lawrenceburg High School stood like an island surrounded by the floodwaters.

Seconds later, he was hit by the huge wave, and his body was carried against the fence at St. Lawrence. There he was found over a month later, his arm still raised toward the sky.

His was the only death directly attributed to the flood.

By 10 a.m., the water had reached Newtown at the corner of Main and Eads Parkway, the first time flood waters had ever been so high.

Forced out of Newtown by the flood, the Emergency Flood Committee had already set up headquarters in the Joseph E. Seagram office, and the next two days were spent in rescuing whole families who had been marooned on the upper stories of their homes. Many people went without heat, water or food for as long as 18 hours as they awaited help.