Page 74 - CA 2019 Final(3)

P. 74

continued from previous page

the secret of their strength is hidden inside: the creators score

lines into one of the layers and spool in galvanized steel wire,

which Phid says can “stretch” a bit more than the concrete. As

the final shaping is done and the screed is pulled away, there

will be no unsightly exterior seam lines.

In the next state, the pots cure in a separate room with mists

and radiant floor heat. Aided by the moisture, crystals grow

through the concrete matrix, giving it strength. Phid says when

the pots leave Lunaform they have 90 percent of the concrete’s

full strength, and that full strength is reached in about 100 years.

After curing, the pots are sandblasted. They may be carved

or decorated at different stages in the process. A “pine cone”

amphora is carved by four people working around it before it

dries. They may texturize the pots with rock salt, tossing it on

randomly and picking it out as the pot dries. Ferns, letters, or

other stencils may be sandblasted into the surface.

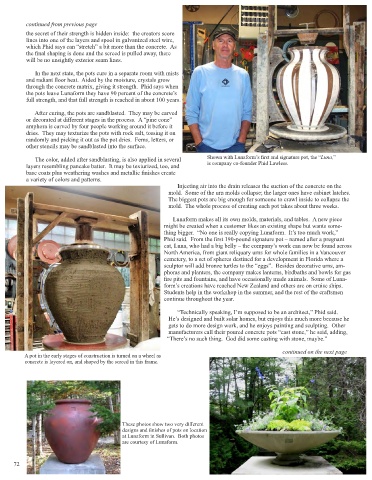

The color, added after sandblasting, is also applied in several Shown with Lunaform’s first and signature pot, the “Luna,”

is company co-founder Phid Lawless.

layers resembling pancake batter. It may be texturized, too, and

base coats plus weathering washes and metallic finishes create

a variety of colors and patterns.

Injecting air into the drain releases the suction of the concrete on the

mold. Some of the urn molds collapse; the larger ones have cabinet latches.

The biggest pots are big enough for someone to crawl inside to collapse the

mold. The whole process of creating each pot takes about three weeks.

Lunaform makes all its own molds, materials, and tables. A new piece

might be created when a customer likes an existing shape but wants some-

thing bigger. “No one is really copying Lunaform. It’s too much work,”

A view of the gallery

Phid said. From the first 190-pound signature pot – named after a pregnant

cat, Luna, who had a big belly – the company’s work can now be found across

North America, from giant reliquary urns for whole families in a Vancouver

cemetery, to a set of spheres destined for a development in Florida where a

sculptor will add bronze turtles to the “eggs”. Besides decorative urns, am-

phoras and planters, the company makes lanterns, birdbaths and bowls for gas

fire pits and fountains, and have occasionally made animals. Some of Luna-

form’s creations have reached New Zealand and others are on cruise ships.

Students help in the workshop in the summer, and the rest of the craftsmen

continue throughout the year.

“Technically speaking, I’m supposed to be an architect,” Phid said.

He’s designed and built solar homes, but enjoys this much more because he

gets to do more design work, and he enjoys painting and sculpting. Other

manufacturers call their poured concrete pots “cast stone,” he said, adding,

“There’s no such thing. God did some casting with stone, maybe.”

continued on the next page

A pot in the early stages of construction is turned on a wheel as

concrete is layered on, and shaped by the screed in this frame.

These photos show two very different

designs and finishes of pots on location

at Lunaform in Sullivan. Both photos

are courtesy of Lunaform.

72