Page 64 - Demo

P. 64

ASPHERIC AND ATORIC SINGLE VISION

It was much later that lenses evolved beyond strictly spherical curves, but the need was there. Spherical lenses provided excellent vision if the most appropriate base curve was used for the patient’s prescription. However, for stronger prescriptions, a spherical lens could be thick and bulgy. One way to address this was to use a lens with a atter front curve. However, since this would not be the ideal front curve for the prescription, the wearer would not have clear vision across the full height and width of the lens (how much it was restricted depended on the patient’s prescription and the curve chosen.) In short, wearers with stronger prescriptions had to choose between the need to see well and the desire to look good.

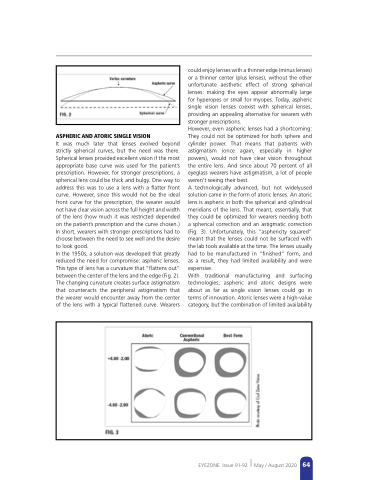

In the 1950s, a solution was developed that greatly reduced the need for compromise: aspheric lenses. This type of lens has a curvature that “ attens out” between the center of the lens and the edge (Fig. 2). The changing curvature creates surface astigmatism that counteracts the peripheral astigmatism that the wearer would encounter away from the center of the lens with a typical attened curve. Wearers

could enjoy lenses with a thinner edge (minus lenses) or a thinner center (plus lenses), without the other unfortunate aesthetic effect of strong spherical lenses: making the eyes appear abnormally large for hyperopes or small for myopes. Today, aspheric single vision lenses coexist with spherical lenses, providing an appealing alternative for wearers with stronger prescriptions.

However, even aspheric lenses had a shortcoming: They could not be optimized for both sphere and cylinder power. That means that patients with astigmatism (once again, especially in higher powers), would not have clear vision throughout the entire lens. And since about 70 percent of all eyeglass wearers have astigmatism, a lot of people weren’t seeing their best.

A technologically advanced, but not widelyused solution came in the form of atoric lenses. An atoric lens is aspheric in both the spherical and cylindrical meridians of the lens. That meant, essentially, that they could be optimized for wearers needing both a spherical correction and an astigmatic correction (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, this “asphericity squared” meant that the lenses could not be surfaced with the lab tools available at the time. The lenses usually had to be manufactured in “ nished” form, and as a result, they had limited availability and were expensive.

With traditional manufacturing and surfacing technologies, aspheric and atoric designs were about as far as single vision lenses could go in terms of innovation. Atoric lenses were a high-value category, but the combination of limited availability

EYEZONE Issue 91-92 May / August 2020 64