Page 35 - Nicolaes Witsen & Shipbuilding in the Dutch Golden Age

P. 35

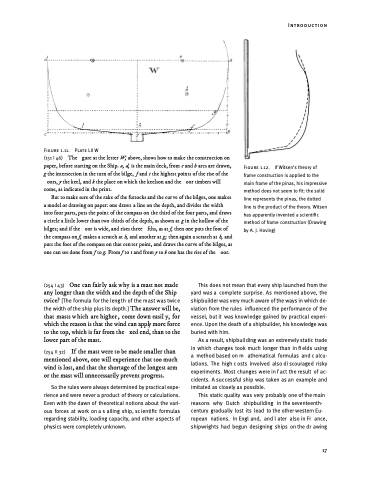

Figure 1.11. Plate LII W

(151 I 46) The gure at the letter W, above, shows how to make the construction on paper, before starting on the Ship. a, d, is the main deck, from e and h arcs are drawn, g the intersection in the turn of the bilge, f and 1 the highest points of the rise of the

oors, y the keel, and k the place on which the keelson and the oor timbers will come, as indicated in the print.

But to make sure of the rake of the futtocks and the curve of the bilges, one makes a model or drawing on paper: one draws a line on the depth, and divides the width into four parts, puts the point of the compass on the third of the four parts, and draws a circle a little lower than two thirds of the depth, as shown at g in the hollow of the bilges; and if the oor is wide, and rises three fths, as at f, then one puts the foot of the compass on f, makes a scratch at h, and another at g; then again a scratch at h, and puts the foot of the compass on that cen ter point, and draws the curve of the bilges, as onecanseedonefromftog.Fromfto1andfromytokonehastheriseofthe oor.

Figure 1.12.

frame construction is applied to the main frame of the pinas, his impressive method does not seem to fit: the solid line represents the pinas, the dotted line is the product of the theory. Witsen has apparently invented a scientific method of frame construction (Drawing by A. J. Hoving)

(254 I 43) One can fairly ask why is a mast not made any longer than the width and the depth of the Ship twice? [The formula for the leng th of the mast was twice the width of the ship plus its depth.] The answer will be, that masts w hich are higher , come down easil y, for whichthereasonisthatthewindcanapplymoreforce to the top, which is far from the xed end, than to the lower part of the mast.

(254 II 32) If the mast were to be made smaller than mentioned above, one will experience that too much wind is lost, and that the shortage of the longest arm or the mast will unnecessarily prevent progress.

So the rules were always determined by practical expe- rience and were never a product of theory or calculations. Even with the dawn of theoretical notions about the vari- ous forces at work on a s ailing ship, sc ientific formulas regarding stability, loading capacity, and other aspects of physics were completely unknown.

This does not mean that every ship launched from the yard was a complete surprise. As mentioned abo ve, the shipbuilder was very much aware of the ways in which de- viation from the rules influenced the per formance of the vessel, but it was knowl edge gained by practical experi- ence.Uponthedeathofashipbuilder,hisknowledgewas buried with him.

As a result, shipbuilding was an extremely static trade in which changes took much longer than in fi elds using a method based on m athematical formulas and c alcu- lations. The high c osts involved also di scouraged risky experiments. Most changes were in f act the result of ac- cidents. A successful ship was taken as an example and imitated as closely as possible.

This static quality was very probably one of the main reasons why Dutch shipbuilding in the seventeenth- century gradually lost its lead to the other western Eu- ropean nations. In Engl and, and l ater also in Fr ance, shipwrights had begun designing ships on the dr awing

Introduction

If Witsen’s theory of

17