Page 13 - 53-Peptic ulcer diseases (Loét dạ dày)

P. 13

CHAPTER 53 Peptic Ulcer Disease 817

The optimal PPI dose to use and the routine of PPI admin- an intention-to-treat analysis, no differences in overall mortality

istration continue to be controversial. A meta-analysis of RCTs rates or duodenal leak rates were seen. These 2 RCTs suggest 53

that compared low- to high-dose PPI use after endoscopic hemo- that simple oversewing with or without vagotomy is associated

stasis consisted of trials that included bleeding ulcers with minor with a higher rate of recurrent bleeding. Exclusion of an ulcer

stigmata of bleeding and clean-based ulcers. 126 The majority of or, in the case of GUs, ulcer excision is important in preventing

studies were underpowered to declare equivalence between low- recurrent bleeding. In a review of data from the American Col-

and high-dose PPI. An international consensus group has contin- lege Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program,

ued to endorse the use of a high-dose PPI, especially in high-risk 30 day mortality was higher in patients who underwent a simple

patients. 104 oversewing or ulcer excision (106/498, 21.3%) when compared to

Pre-emptive use of an IV PPI infusion prior to endoscopy was that after vagotomy with resection or drainage (39/283, 13.8%).

studied in a large-scale randomized study. 127 Patients with overt There was obvious bias in this retrospective analysis. 134

signs of UGI bleeding were randomized to receive either a high-

dose PPI infusion or placebo. Most (60%) of the patients in this Angiographic Therapy

cohort were found at EGD to be bleeding from a peptic ulcer.

The study demonstrated that early PPI infusion down-staged Angiographic embolization of bleeding arteries is a nonoperative

endoscopic bleeding stigmata in patients with peptic ulcers and alternative to surgery in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer. In a

thereby reduced the need for endoscopic therapy; thus, there pooled analysis of 6 retrospective studies comparing angiography

were fewer ulcers with active bleeding or with major stigmata and surgery, a higher re-bleeding rate was observed after angio-

of recent hemorrhage observed during the following morning’s graphic treatment (51/178, or 29% vs. 36/241, or 15%; RR 1.82;

EGD in the PPI group. PPI infusion starts ulcer healing, and 95% CI, 1.20 to 2.67). 135 Mortality was not significantly different

significantly more clean-based ulcers are seen the next day. The (17% vs. 23%). When radiology skills are available, angiography

study has cost-saving implications, with less endoscopic therapy is often attempted before surgery. A recent RCT that compared

required with the preemptive use of an IV PPI. In patients await- added embolization to standard treatment after endoscopic hemo-

ing endoscopy, it is reasonable to start PPI therapy. stasis did not confirm a mortality benefit of prophylactic emboliza-

tion. 136 In a per protocol analysis, rate of further bleeding was lower

Surgical Therapy after added embolization (6/96, or 6.2% vs. 14/123, or 11.4%). In a

subgroup analysis of ulcers of 15 mm or more in size, embolization

Effective endoscopic intervention and improved pharmacother- reduced bleeding from 23.1% to 4.5%. The authors suggested that

apy have greatly reduced the need for emergency ulcer surgery. for larger ulcers with significant bleeding, angiographic emboliza-

In the USA, the incidence of surgery to control ulcer bleeding tion should be considered after endoscopic hemostasis.

has continued to decline (from 13.1% in 1993 to 9.7% in 2006),

while there was an increase in the use of endoscopic treatment Perforation

(12.9% to 22.2%). 128 In an UK National Audit in 2006, only 2.3%

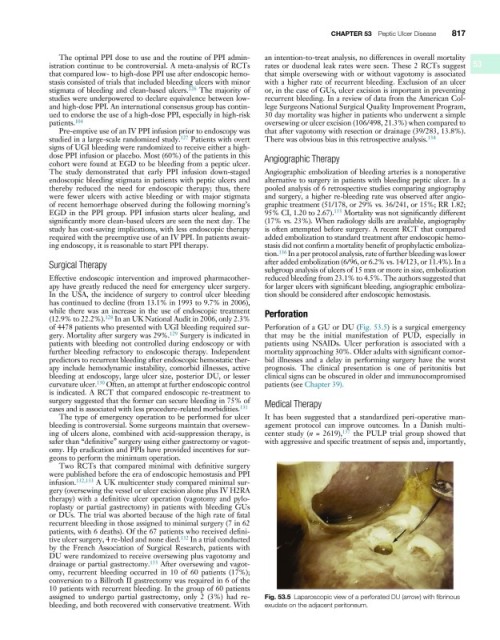

of 4478 patients who presented with UGI bleeding required sur- Perforation of a GU or DU (Fig. 53.5) is a surgical emergency

gery. Mortality after surgery was 29%. 129 Surgery is indicated in that may be the initial manifestation of PUD, especially in

patients with bleeding not controlled during endoscopy or with patients using NSAIDs. Ulcer perforation is associated with a

further bleeding refractory to endoscopic therapy. Independent mortality approaching 30%. Older adults with significant comor-

predictors to recurrent bleeding after endoscopic hemostatic ther- bid illnesses and a delay in performing surgery have the worst

apy include hemodynamic instability, comorbid illnesses, active prognosis. The clinical presentation is one of peritonitis but

bleeding at endoscopy, large ulcer size, posterior DU, or lesser clinical signs can be obscured in older and immunocompromised

curvature ulcer. 130 Often, an attempt at further endoscopic control patients (see Chapter 39).

is indicated. A RCT that compared endoscopic re-treatment to

surgery suggested that the former can secure bleeding in 75% of Medical Therapy

cases and is associated with less procedure-related morbidities. 131

The type of emergency operation to be performed for ulcer It has been suggested that a standardized peri-operative man-

bleeding is controversial. Some surgeons maintain that oversew- agement protocol can improve outcomes. In a Danish multi-

ing of ulcers alone, combined with acid-suppression therapy, is center study (n = 2619), 137 the PULP trial group showed that

safer than “definitive” surgery using either gastrectomy or vagot- with aggressive and specific treatment of sepsis and, importantly,

omy. Hp eradication and PPIs have provided incentives for sur-

geons to perform the minimum operation.

Two RCTs that compared minimal with definitive surgery

were published before the era of endoscopic hemostasis and PPI

infusion. 132,133 A UK multicenter study compared minimal sur-

gery (oversewing the vessel or ulcer excision alone plus IV H2RA

therapy) with a definitive ulcer operation (vagotomy and pylo-

roplasty or partial gastrectomy) in patients with bleeding GUs

or DUs. The trial was aborted because of the high rate of fatal

recurrent bleeding in those assigned to minimal surgery (7 in 62

patients, with 6 deaths). Of the 67 patients who received defini-

tive ulcer surgery, 4 re-bled and none died. 132 In a trial conducted

by the French Association of Surgical Research, patients with

DU were randomized to receive oversewing plus vagotomy and

drainage or partial gastrectomy. 133 After oversewing and vagot-

omy, recurrent bleeding occurred in 10 of 60 patients (17%);

conversion to a Billroth II gastrectomy was required in 6 of the

10 patients with recurrent bleeding. In the group of 60 patients

assigned to undergo partial gastrectomy, only 2 (3%) had re- Fig. 53.5 Laparoscopic view of a perforated DU (arrow) with fibrinous

bleeding, and both recovered with conservative treatment. With exudate on the adjacent peritoneum.