Page 22 - Gastrointestinal Bleeding (Xuất huyết tiêu hóa)

P. 22

296 PART III Symptoms, Signs, and Biopsychosocial Issues

the risk of metastasis. Angiography with embolization should has been associated with cirrhosis and systemic sclerosis (sclero-

be considered for patients with severe UGI bleeding caused by derma) (see Chapters 37, 38, and 92). Patients with GAVE who do

malignancy who do not respond to endoscopic therapy. External not have portal hypertension demonstrate linear arrays of angio-

beam radiation can provide palliative hemostasis for patients with mas (classic GAVE), whereas those with portal hypertension have

bleeding from advanced gastric or duodenal cancer (see Chapter more diffuse antral angiomas. 196 The diffuse type of antral angio-

54). Hemospray has been used to manage oozing bleeding from mas and, occasionally, classic GAVE are sometimes mistaken for

42

UGI tumors in a small case series (see earlier). gastritis by an unsuspecting endoscopist. Such cases are a common

cause of obscure GI bleeding in referral centers (see later). 57

GAVE Patients usually present with iron deficiency anemia or melena,

with a mildly decreased hematocrit value suggestive of a slow

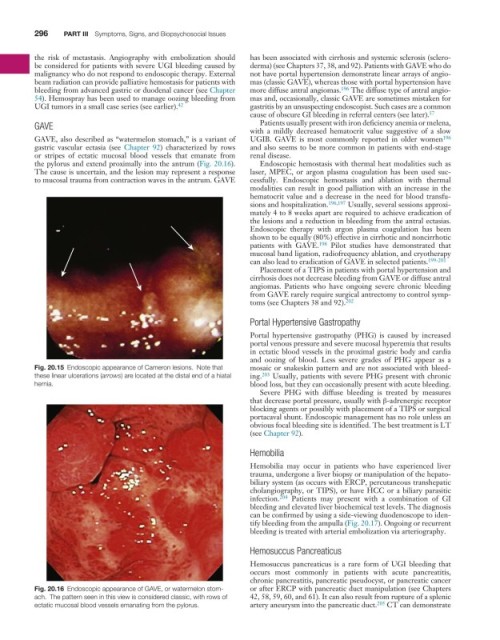

GAVE, also described as “watermelon stomach,” is a variant of UGIB. GAVE is most commonly reported in older women 196

gastric vascular ectasia (see Chapter 92) characterized by rows and also seems to be more common in patients with end-stage

or stripes of ectatic mucosal blood vessels that emanate from renal disease.

the pylorus and extend proximally into the antrum (Fig. 20.16). Endoscopic hemostasis with thermal heat modalities such as

The cause is uncertain, and the lesion may represent a response laser, MPEC, or argon plasma coagulation has been used suc-

to mucosal trauma from contraction waves in the antrum. GAVE cessfully. Endoscopic hemostasis and ablation with thermal

modalities can result in good palliation with an increase in the

hematocrit value and a decrease in the need for blood transfu-

sions and hospitalization. 196,197 Usually, several sessions approxi-

mately 4 to 8 weeks apart are required to achieve eradication of

the lesions and a reduction in bleeding from the antral ectasias.

Endoscopic therapy with argon plasma coagulation has been

shown to be equally (80%) effective in cirrhotic and noncirrhotic

patients with GAVE. 198 Pilot studies have demonstrated that

mucosal band ligation, radiofrequency ablation, and cryotherapy

can also lead to eradication of GAVE in selected patients. 199-201

Placement of a TIPS in patients with portal hypertension and

cirrhosis does not decrease bleeding from GAVE or diffuse antral

angiomas. Patients who have ongoing severe chronic bleeding

from GAVE rarely require surgical antrectomy to control symp-

toms (see Chapters 38 and 92). 202

Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

Portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) is caused by increased

portal venous pressure and severe mucosal hyperemia that results

in ectatic blood vessels in the proximal gastric body and cardia

and oozing of blood. Less severe grades of PHG appear as a

Fig. 20.15 Endoscopic appearance of Cameron lesions. Note that mosaic or snakeskin pattern and are not associated with bleed-

these linear ulcerations (arrows) are located at the distal end of a hiatal ing. 203 Usually, patients with severe PHG present with chronic

hernia. blood loss, but they can occasionally present with acute bleeding.

Severe PHG with diffuse bleeding is treated by measures

that decrease portal pressure, usually with β-adrenergic receptor

blocking agents or possibly with placement of a TIPS or surgical

portacaval shunt. Endoscopic management has no role unless an

obvious focal bleeding site is identified. The best treatment is LT

(see Chapter 92).

Hemobilia

Hemobilia may occur in patients who have experienced liver

trauma, undergone a liver biopsy or manipulation of the hepato-

biliary system (as occurs with ERCP, percutaneous transhepatic

cholangiography, or TIPS), or have HCC or a biliary parasitic

infection. 204 Patients may present with a combination of GI

bleeding and elevated liver biochemical test levels. The diagnosis

can be confirmed by using a side-viewing duodenoscope to iden-

tify bleeding from the ampulla (Fig. 20.17). Ongoing or recurrent

bleeding is treated with arterial embolization via arteriography.

Hemosuccus Pancreaticus

Hemosuccus pancreaticus is a rare form of UGI bleeding that

occurs most commonly in patients with acute pancreatitis,

chronic pancreatitis, pancreatic pseudocyst, or pancreatic cancer

Fig. 20.16 Endoscopic appearance of GAVE, or watermelon stom- or after ERCP with pancreatic duct manipulation (see Chapters

ach. The pattern seen in this view is considered classic, with rows of 42, 58, 59, 60, and 61). It can also result from rupture of a splenic

ectatic mucosal blood vessels emanating from the pylorus. artery aneurysm into the pancreatic duct. 205 CT can demonstrate