Page 506 - Physics Coursebook 2015 (A level)

P. 506

Cambridge International A Level Physics

494

The minimum energy needed to pull a nucleus apart into its separate nucleons is known as the binding energy of the nucleus.

QUESTIONS

We can calculate the energy released in all decay reactions, including β-decay, using the same ideas as above.

QUESTION

10

8 Anucleusofberyllium 4Bedecaysintoanisotope

of boron by β−-emission. The chemical symbol for boron is B.

a Write a nuclear decay equation for the nucleus of beryllium-10.

b Calculate the energy released in this decay and state its form.

mass of 140Be nucleus = 1.662 38 × 10−26 kg mass of boron isotope = 1.662 19 × 10−26 kg mass of electron = 9.109 56 × 10−31 kg

Binding energy and stability

We can now begin to see why some nuclei are more stable than others. If a nucleus is formed from separate nucleons, energy is released. In order to pull the nucleus apart, energy must be put in; in other words, work must be done against the strong nuclear force which holds the nucleons together. The more energy involved in this, the more stable is the nucleus.

Take care: this is not energy stored in the nucleus; on the contrary, it is the energy that must be put in to the nucleus

12

in order to pull it apart. In the example of 6C discussed

above, we calculated the binding energy from the mass difference between the mass of the 126C nucleus and the masses of the separate protons and neutrons.

In order to compare the stability of different nuclides, we need to consider the binding energy per nucleon.

We can determine the binding energy per nucleon for a nuclide as follows:

■■ Determine the mass defect for the nucleus.

■■ Use Einstein’s mass–energy equation to determine the

binding energy of the nucleus by multiplying the mass

defect by c2.

■■ Divide the binding energy of the nucleus by the number of nucleons to calculate the binding energy per nucleon.

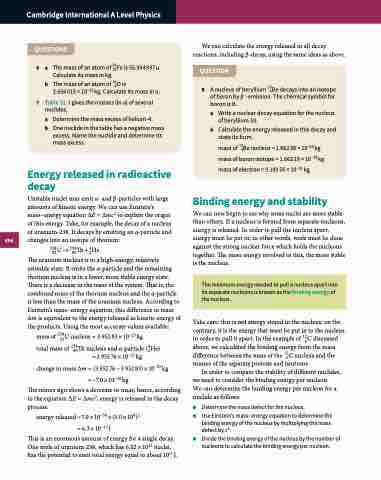

The mass of an atom of 56Fe is 55.934 937 u. 26

6 a

b The mass of an atom of 168O is

Calculate its mass in kg.

2.656 015 × 10−26 kg. Calculate its mass in u.

7 Table 31.3 gives the masses (in u) of several nuclides.

a Determine the mass excess of helium-4.

b One nuclide in the table has a negative mass excess. Name the nuclide and determine its mass excess.

Energy released in radioactive decay

Unstable nuclei may emit α- and β-particles with large amounts of kinetic energy. We can use Einstein’s mass–energy equation ΔE = Δmc2 to explain the origin of this energy. Take, for example, the decay of a nucleus of uranium-238. It decays by emitting an α-particle and changes into an isotope of thorium:

238U→234Th+4He 92 90 2

The uranium nucleus is in a high-energy, relatively unstable state. It emits the α-particle and the remaining thorium nucleus is in a lower, more stable energy state. There is a decrease in the mass of the system. That is, the combined mass of the thorium nucleus and the α-particle is less than the mass of the uranium nucleus. According to Einstein’s mass–energy equation, this difference in mass Δm is equivalent to the energy released as kinetic energy of the products. Using the most accurate values available:

mass of 238U nucleus = 3.952 83 × 10−25 kg 92

total mass of 234Th nucleus and α-particle (4He) 90 =3.95276×10−25 kg 2

change in mass Δm = (3.952 76 − 3.952 83) × 10−25 kg ≈−7.0×10−30kg

The minus sign shows a decrease in mass, hence, according to the equation ΔE = Δmc2, energy is released in the decay process:

energy released ≈ 7.0 × 10−30 × (3.0 × 108)2

−13 ≈6.3×10 J

This is an enormous amount of energy for a single decay. One mole of uranium-238, which has 6.02 × 1023 nuclei, has the potential to emit total energy equal to about 1011 J.