Page 353 - Krugmans Economics for AP Text Book_Neat

P. 353

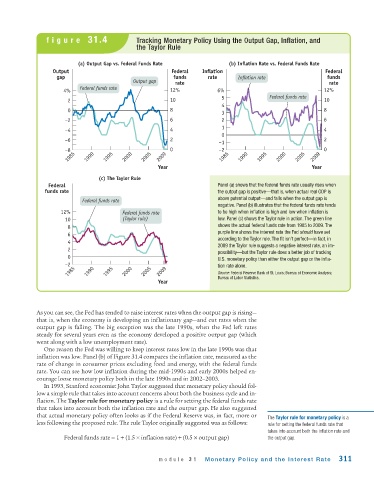

figure 31.4 Tracking Monetary Policy Using the Output Gap, Inflation, and

the Taylor Rule

(a) Output Gap vs. Federal Funds Rate (b) Inflation Rate vs. Federal Funds Rate

Output Federal Inflation Federal

gap funds rate Inflation rate funds

Output gap rate rate

4% Federal funds rate 12% 6% 12%

2 10 5 Federal funds rate 10

4

0 8 3 8

–2 6 2 6

–4 4 1 4

0

–6 2 –1 2

–8 0 –2 0

1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2009 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2009

Year Year

(c) The Taylor Rule

Federal Panel (a) shows that the federal funds rate usually rises when

funds rate the output gap is positive—that is, when actual real GDP is

above potential output—and falls when the output gap is

Federal funds rate

negative. Panel (b) illustrates that the federal funds rate tends

12% Federal funds rate to be high when inflation is high and low when inflation is

10 (Taylor rule) low. Panel (c) shows the Taylor rule in action. The green line

8 shows the actual federal funds rate from 1985 to 2009. The

6 purple line shows the interest rate the Fed should have set

4 according to the Taylor rule. The fit isn’t perfect—in fact, in

2 2009 the Taylor rule suggests a negative interest rate, an im-

possibility—but the Taylor rule does a better job of tracking

0 U.S. monetary policy than either the output gap or the infla-

–2 tion rate alone.

1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2009 Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; Bureau of Economic Analysis;

Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Year

As you can see, the Fed has tended to raise interest rates when the output gap is rising—

that is, when the economy is developing an inflationary gap—and cut rates when the

output gap is falling. The big exception was the late 1990s, when the Fed left rates

steady for several years even as the economy developed a positive output gap (which

went along with a low unemployment rate).

One reason the Fed was willing to keep interest rates low in the late 1990s was that

inflation was low. Panel (b) of Figure 31.4 compares the inflation rate, measured as the

rate of change in consumer prices excluding food and energy, with the federal funds

rate. You can see how low inflation during the mid-1990s and early 2000s helped en-

courage loose monetary policy both in the late 1990s and in 2002–2003.

In 1993, Stanford economist John Taylor suggested that monetary policy should fol-

low a simple rule that takes into account concerns about both the business cycle and in-

flation. The Taylor rule for monetary policy is a rule for setting the federal funds rate

that takes into account both the inflation rate and the output gap. He also suggested

that actual monetary policy often looks as if the Federal Reserve was, in fact, more or The Taylor rule for monetary policy is a

less following the proposed rule. The rule Taylor originally suggested was as follows: rule for setting the federal funds rate that

takes into account both the inflation rate and

Federal funds rate = 1 + (1.5 × inflation rate) + (0.5 × output gap) the output gap.

module 31 Monetary Policy and the Interest Rate 311