Page 263 - Geosystems An Introduction to Physical Geography 4th Canadian Edition

P. 263

60

(b)

(103)

41

(53) (61)

29

PACIFIC OCEAN

120°

0.5–0.9 1.0–2.9 3.0–4.9 5.0–6.9 7.0–8.9

More than 9.0

(95)

60

135

PACIFIC CANADA OCEAN

CANADA

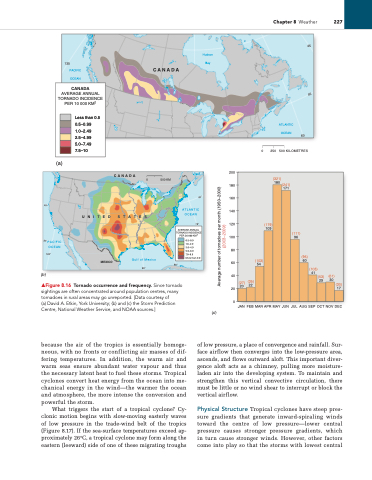

AVERAGE ANNUAL TORNADO INCIDENCE PER 10 000 KM2

Less than 0.5 0.5–0.99 1.0–2.49 2.5–4.99 5.0–7.49 7.5–10

Hudson Bay

(a)

MEXICO

Gulf of Mexico

90°

80°

(103)

54

CANADA

0

500 KM

200 180 160 140 120 100

80 60 40 20

(321)

180 (241)

171

UNITED STATES

ATLANTIC OCEAN

70°

AVERAGE ANNUAL TORNADO INCIDENCE

▲Figure 8.16 Tornado occurrence and frequency. Since tornado sightings are often concentrated around population centres, many tornadoes in rural areas may go unreported. [Data courtesy of

(a) David A. etkin, york University; (b) and (c) the Storm Prediction Centre, National Weather Service, and NOAA sources.]

because the air of the tropics is essentially homoge- neous, with no fronts or conflicting air masses of dif- fering temperatures. In addition, the warm air and warm seas ensure abundant water vapour and thus the necessary latent heat to fuel these storms. Tropical cyclones convert heat energy from the ocean into me- chanical energy in the wind—the warmer the ocean and atmosphere, the more intense the conversion and powerful the storm.

What triggers the start of a tropical cyclone? Cy- clonic motion begins with slow-moving easterly waves of low pressure in the trade-wind belt of the tropics (Figure 8.17). If the sea-surface temperatures exceed ap- proximately 26°C, a tropical cyclone may form along the eastern (leeward) side of one of these migrating troughs

(30)

17

PER 26 000 KM

2

(111)

96

0 (c)

20 22

JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEP OCT NOV DEC

(27) (35)

30

0

250 500 KILOMETRES

(179)

109

of low pressure, a place of convergence and rainfall. Sur- face airflow then converges into the low-pressure area, ascends, and flows outward aloft. This important diver- gence aloft acts as a chimney, pulling more moisture- laden air into the developing system. To maintain and strengthen this vertical convective circulation, there must be little or no wind shear to interrupt or block the vertical airflow.

Physical Structure Tropical cyclones have steep pres- sure gradients that generate inward-spiraling winds toward the centre of low pressure—lower central pressure causes stronger pressure gradients, which in turn cause stronger winds. However, other factors come into play so that the storms with lowest central

Chapter 8 Weather

227

45

45

ATLANTIC OCEAN

60

45

40°

40°

30°

Average number of tornadoes per month (1950–2000)

(2003–2009)