Page 590 - Geosystems An Introduction to Physical Geography 4th Canadian Edition

P. 590

554 part III The earth–atmosphere interface

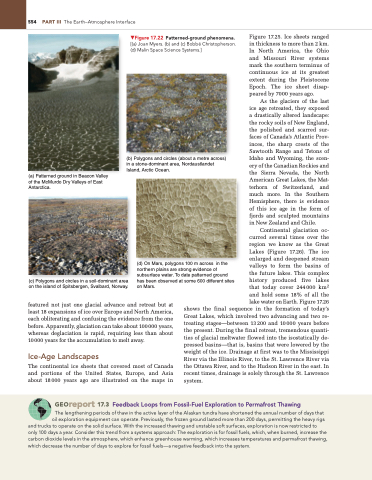

▼Figure 17.22 Patterned-ground phenomena. [(a) Joan Myers. (b) and (c) Bobbé Christopherson. (d) Malin Space Science Systems.]

(b) Polygons and circles (about a metre across) in a stone-dominant area, Nordaustlandet Island, Arctic Ocean.

Figure 17.25. Ice sheets ranged in thickness to more than 2 km. In North America, the Ohio and Missouri River systems mark the southern terminus of continuous ice at its greatest extent during the Pleistocene Epoch. The ice sheet disap- peared by 7000 years ago.

As the glaciers of the last ice age retreated, they exposed a drastically altered landscape: the rocky soils of New England, the polished and scarred sur- faces of Canada’s Atlantic Prov- inces, the sharp crests of the Sawtooth Range and Tetons of Idaho and Wyoming, the scen- ery of the Canadian Rockies and the Sierra Nevada, the North American Great Lakes, the Mat- terhorn of Switzerland, and much more. In the Southern Hemisphere, there is evidence of this ice age in the form of fjords and sculpted mountains in New Zealand and Chile.

Continental glaciation oc- curred several times over the region we know as the Great Lakes (Figure 17.26). The ice enlarged and deepened stream valleys to form the basins of the future lakes. This complex history produced five lakes that today cover 244000 km2 and hold some 18% of all the lake water on Earth. Figure 17.26

(a) Patterned ground in Beacon Valley of the McMurdo Dry Valleys of East Antarctica.

(c) Polygons and circles in a soil-dominant area on the island of Spitsbergen, Svalbard, Norway.

(d) On Mars, polygons 100 m across in the northern plains are strong evidence of subsurface water. To date patterned ground has been observed at some 600 different sites on Mars.

featured not just one glacial advance and retreat but at least 18 expansions of ice over Europe and North America, each obliterating and confusing the evidence from the one before. Apparently, glaciation can take about 100000 years, whereas deglaciation is rapid, requiring less than about 10000 years for the accumulation to melt away.

Ice-Age Landscapes

The continental ice sheets that covered most of Canada and portions of the United States, Europe, and Asia about 18000 years ago are illustrated on the maps in

shows the final sequence in the formation of today’s Great Lakes, which involved two advancing and two re- treating stages—between 13200 and 10000 years before the present. During the final retreat, tremendous quanti- ties of glacial meltwater flowed into the isostatically de- pressed basins—that is, basins that were lowered by the weight of the ice. Drainage at first was to the Mississippi River via the Illinois River, to the St. Lawrence River via the Ottawa River, and to the Hudson River in the east. In recent times, drainage is solely through the St. Lawrence system.

Georeport 17.3 Feedback Loops from Fossil-Fuel Exploration to Permafrost Thawing

The lengthening periods of thaw in the active layer of the alaskan tundra have shortened the annual number of days that oil exploration equipment can operate. Previously, the frozen ground lasted more than 200 days, permitting the heavy rigs

and trucks to operate on the solid surface. With the increased thawing and unstable soft surfaces, exploration is now restricted to only 100 days a year. Consider this trend from a systems approach: The exploration is for fossil fuels, which, when burned, increase the carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, which enhance greenhouse warming, which increases temperatures and permafrost thawing, which decrease the number of days to explore for fossil fuels—a negative feedback into the system.