Page 259 - Neglected Arabia Vol 1 (2)

P. 259

1

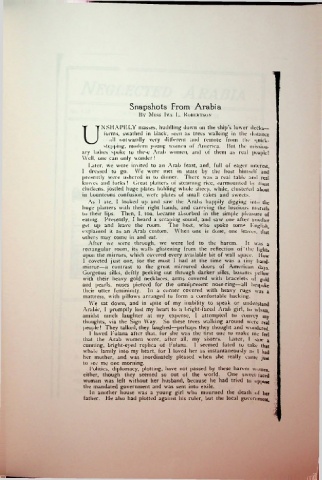

Snapshots From Arabia

By Miss Iva L. Koiikktson

U NSHAPELY masses, huddling down on the ship’s lower decks—

forms, swathed in black, seen as trees walking in the distance

• all outwardly very diHerein and remote from tin- <|uiek«

stepping, modern young women of America. But the mission

ary ladies spoke to these Arab women, and of them as real people 1

Well, one can only wonder!

Later, we were invited to an Arab feast, and, full of eager interest,

1 dressed to go. We were met in state by the host himself and

presently were ushered in to dinner. There was a real table and real

knives and forks! Great platters of steaming rice, surmounted by roast

chickens, jostled huge plates holding whole sheep, while, clustered about

in bounteous confusion, were plates of small cakes and sweets.

As 1 ate, I looked up and saw the Arabs happily digging into the

huge platters with their right hands, and carrying the luscious morsels

to their lips. Then, 1, too, became absorbed in the simple pleasure of

eating. Presently, I heard a scraping sound, and saw one after another

get up and leave the room. The host, who spoke some KnglLh,

explained it as an Arab custom. When one is done, one leaves, that

others may come in and eat.

After we were through, we were led to the harem. It was a

rectangular room, its walls glistening from the reflection of the lights

upon the mirrors, which covered every available bit of wall space. How

I coveted just one, tor the most 1 had at the time was a liny hand,

mirror—a contrast to the great mirrored doors of American day*.

Gorgeous silks, deftly peeking out through darker silks, bosoms yellow

with their heavy gold necklaces, arms covered with bracelets of g()|d

and pearls, noses pierced for the omnipresent nose-ring—all bespoke

their utter femininity. In a corner covered with heavy rugs was a

mattress, with pillows arranged to form a comfortable backing.

We sat down, and in spite of my inability to speak or understand

Arabic, I promptly lost my heart to a bright-faced Arab girl, to whom,

amidst much laughter at my expense, l attempted to convey my

thoughts, via the Sign Way. So these trees walking around were real

people! They talked, they laughed—perhaps they thought and wondered.

I loved Fulana after that, for she was the first one to make me feel

that the Arab women were, after all, my sisters. l-ater, 1 saw a

cunning, briglu-eyed replica of Fulana. 1 seemed fated to take that

whole family into my heart, for I loved her as instantaneously as 1 had

her mother, and was inordinately pleased when she really came ju>i

to see me one morning.

Politics, diplomacy, plotting-, have not passed by these harem women,

either, though they seemed so out of the world. One sweel-fuccd

woman was left without her husband, because he had tried to uppo* ’

the mandated government and was sent into exile.

In another house was a young girl who mourned the death of her

father. He also had plotted against his ruler, but the local government.

A

;