Page 19 - Nov 2019 Christie's Hong Kong a Falancai Imperial Bowl.

P. 19

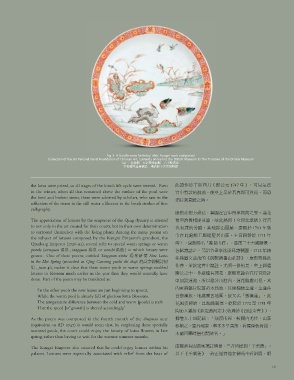

fig. 3 A famille verte ‘birthday‘ dish, Kangxi mark and period

Collection of the Sir Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, currently on loan to the British Museum © The Trustees of the British Museum

எӲ ᳖ᄮᾭ Նᆭ⸥ᮆஎ⏎ ݪໃᥓᝧ᪪

ഌヵᇪఫ㞖ᝯ⻦ →٨ཿԽഌⲖࢷ⁒㱦

the lotus were prized, so all stages of the lotus’s life cycle were revered. Even ᫉㉼הᙻӭࣆ୨ᝲ卻࣊ݩ݉ ჺ卼卿ज㘺Ջ

in the winter, when all that remained above the surface of the pool were ༈ԋ⁞㉑⎏ᵐᮆ卿ײ⎑ӳᙻᜰᛌ࣊ज㐃卿⩧ᬑ

the bent and broken stems, these were admired by scholars, who saw in the

㮷ᇅߪᜠԠᛞǯ

reflection of the stems in the still water a likeness to the brush strokes of fine

calligraphy.

ᄮᾭՔዏᙹ㉑ᯧ卿ݴஎங༈ԋᇑՖ㐃Ԡᦼǯ⸥Ɽ

The appreciation of lotuses by the emperors of the Qing dynasty is attested ⯝ᱲ⏟ᓽԆ㋏卿ᘢ᫉ῂᯇ卻իᯇ࢈ᐂᇪ卼リ༈

to not only in the art created for their courts, but in their own determination

Ԯᝳ⸥⎏ⱥ㔌ǯ⋁⨍ྒྷஉ⥴卿ᄮᾭᙻ ჺᘬ

to surround themselves with the living plants. Among the many poems on

ռங᫉⽔࡚႙⯞ᅤ㚈ྒྷⴃǯԖ༈ᬆ⨍ᙻ ჺ

the subject of lotuses composed by the Kangxi Emperor’s grandson, the

Qianlong Emperor (1736-95), several refer to special warm springs or warm ⛎႙卿ᄮᾭ㐁लǸ㚈ྒྷⴃǹ卿Ԇ㚁Ӳࢦݪ⽔ࡠᜀ卿

ponds (wenquan ᳪᯛ , tangquan ᴨᯛ or wenchi ᳪᮆ ) in which lotuses were प㐋㉼㊗Ԡ卿औ㉭ռ⊺།ᮨ္ἃ㉼ㅳஎ卿 ჺ⢙

grown. One of these poems, entitled Tangquan xinhe ᴨᯛᙲ New Lotus

㫀ἃஎᙔԆⲧ⎏Ƕᇙㅳ㚈ྒྷⴃ㉼Ƿ卿ᄮᾭ⁞ἃ᫉

in the Hot Spring (recorded in Qing Gaozong yuzhi shi chuji ᳖㵶ᇙㅳ㉼ߝ

הᄑ卿Ԇ᪩ᝧԋ㯪㉙ǯཝ㮷Ӭᓽ⎏ᛓ卿⎑ӳᇙ㚁

㫀 , juan 40, makes it clear that these warm pools or warm springs enabled

lotuses to blossom much earlier in the year than they would naturally have ࡠᜀԠԋ卿അ⽔ᝳ⸥Ɽ卿ᄮᾭᝤ㋢ռஙリ༈㉑㈷

done. Part of the poem may be translated as: ԋ࠼㉑⸥ᮆ卿Ꮢս㚈ྒྷⴃݤ卿⸥Ɽ㪪⽔जǯ༈

ݤᝤཆᙃ‷㩴ⶔ⸆᭢ἃᮆ卿ս؝♎㞖⸥ǯ㞖⸥⊄

‘In the other pools the new leaves are just beginning to sprout,

While the warm pool is already full of glorious lotus blossoms. ⯇ᘭᶴᚐ卿⽔ⷡऒࢥ卿ᘢࣽलǸᘭᶴ⸥ǹ卿᫉

The temperature difference between the cold and warm [pools] is such Ɽ㰍න⣯⡙卿ӻ㯄ἃ⩫༠ǯԳ㪏ᙻ ⯍ ჺ

That the speed [of growth] is altered accordingly.’

㧿উ՞⤔⦕Ƕ᪩ῂᯇሂǷ ᘘ㢙ᙻǶ୨ᄣݥᝧǷ卼卿

As the poem was composed in the fourth month of the dingmao year ᗌ࣍Ԭࢦ୨㉃㖊厍ǸᘭᶴᏒ⊄卿㖅㨸ݤཝצ卿ྒྷⴃ

(equivalent to AD 1747) it would seem that, by employing these specially ☭Ԡǯ౻ം༠卿Ⳟណഅ㿩ⶔ卿ℒ᳅☌བ㧷卿

warmed pools, the court could enjoy the beauty of lotus flowers in late

ណ⼵୪㓾ᛞ⃫ᝳ㧷ᘞ⩢ǯǹ

spring, rather than having to wait for the warmer summer months.

The Kangxi Emperor also ensured that he could enjoy lotuses within his ᄮᾭႽᝳ୨㲛ঘ⸥㉼۔ӽ卿Ӳ⩢⎐ᓽߪǸࢨ⸥ǹǯ

palaces. Lotuses were especially associated with relief from the heat of սӴǶࢨ⸥ǷӬ㉼᫈ᛓ༵ձஙᇙⱹஶ⏭ᙢ㪈卿␓

19