Page 63 - Christie's Hong Kong Important Chinese Works Of Art May 30 2022

P. 63

Kuchikiri-no-chaji (literally ‘mouth cutting tea ceremony’) is held in Such was the value placed on the current jar, and those similarly used

early November. Before the ceremony the bamboo hedges and water for the leaf tea of the kuchikiri-no-chaji ceremony, that valuable Ming

troughs in the garden of the tea room are replaced. In the tea room dynasty brocades were used to provide the decorative top covers of

itself, the paper of the shoji sliding doors is replaced and new tatami the jar. As noted above, several layers of paper were used beneath the

mats are put on the floor. In preparation for the ceremony, the tea leaf silk cover, which would have protected the precious brocade. The top

jar is given a fine silk cover called a kuchioi held in place with covers themselves are significant and valuable items, which

a decorative rope called a kazario. During the ceremony the add greatly to the important history of the jar. Each cover

silk fabric cover is carefully removed, the paper is cut preserved with the current jar is made of a different silk

and the wooden plug taken out to provide access fabric, two of them including so-called ‘flat-gold’

to the tea inside the jar. The new tea leaves are weft threads.

ground into powder with a pestle in a stone

mortar before being used to prepare the tea. The beautiful cloud-patterned damask cover

(fig. 2) represents a design which was especially

It is very rare that a Longquan celadon jar popular in the Ming dynasty, and became

is used for this purpose, however, there are famous as Nanjing yunjin. It was sometimes

some historical references to such jars. A letter used for the clothing of members of the Chinese

from the famous tea master Sen-no-Rikyu aristocracy, and a robe made from a yellow silk

to Shunoku Soen (1529-1611), abbot of the satin damask with this design was excavated

Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto, described the tea from the tomb of Wang Zhiyuan – a relative of

utensils used in a tea ceremony held by Toyotomi Lady Wang, who was Xiaozhen Empress to the

Hideyoshi (1537-98) at the emperor’s palace on 7th Chenghua Emperor (r. 1465-87) – which was found

October 1585. Sen-no-Rikyu noted: ‘...a kinuta tea outside the Zhonghua Gate, Nanjing (illustrated in

leaf jar in a net under the floor’. Kinuta in this instance Power and Glory: Court Arts of China’s Ming Dynasty,

refers to Longquan celadon, as this was the term used San Francisco, 2008, p. 70, no. 30).

for the fine Longquan glaze which was associated

in Japan with kinuta (mallet-shaped) vases. In the late Yuan and Ming dynasty the yunjing

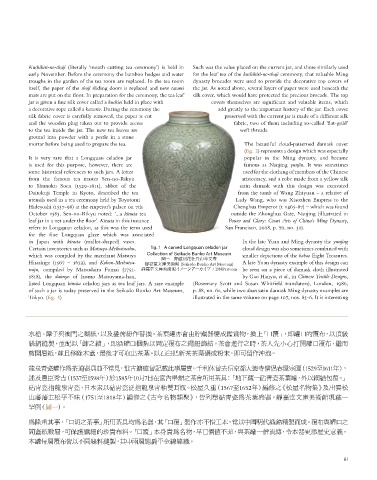

Certain inventories such as Matsuya-Meibutsushu, fig. 1 A carved Longquan celadon jar cloud design was also sometimes combined with

which was compiled by the merchant Matsuya Collection of Seikado Bunko Art Museum smaller depictions of the babao Eight Treasures.

圖一 青磁刻花牡丹唐草文壺

Hisashige (1567 – 1652), and Kokon-Meibutsu- 靜嘉堂文庫美術館 (Seikado Bunko Art Museum) A late Yuan dynasty example of this design can

ruiju, compiled by Matsudaira Fumai (1751- 靜嘉堂文庫美術館イメージアーカイブ / DNPartcom be seen on a piece of damask cloth illustrated

1818), the daimyo of Izumo Matsuyama-han, by Gao Hanyu, et al., in Chinese Textile Designs,

listed Longquan kinuta celadon jars as tea leaf jars. A rare example (Rosemary Scott and Susan Whitfield translators), London, 1986,

of such a jar is today preserved in the Seikado Bunko Art Museum, p. 88, no. 61, while two duan satin damask Ming dynasty examples are

Tokyo. (fig. 1) illustrated in the same volume on page 107, nos. 85-6. It is interesting

水槽、障子與襖門之糊紙,以及疊蓆紛作替換。茶葉罐亦會由貯藏器變成鑑賞物,換上「口覆」,即罐口的覆布,以頂級

絲綢縫製,並配以「飾之緒」,即沿罐口捆紮以固定覆布之繩鈕飾結。茶會進行之時,茶人先小心打開罐口覆布,繼而

剪開層紙,並且移除木蓋,最後才可取出茶葉。以石臼把新茶茶葉碾成粉末,即可留作沖泡。

龍泉青瓷罐作為茶道器具並不常見,惟古籍確曾記載此事屬實。千利休曾去信京都大德寺僧侶春屋宗園(1529至1611年),

述及豐臣秀吉(1537至1598年)於1585年10月7日在宮內舉辦之茶會所用茶具:「地下藏一砧青瓷茶葉罐,外以網結包覆。」

砧青瓷指龍泉青瓷,日本素以砧青瓷泛指龍泉青釉雙耳瓶。松屋久重(1567至1652年)編修之《松屋名物集》及出雲松

山藩藩主松平不昧(1751至1818年)編修之《古今名物類聚》,皆列舉砧青瓷為茶葉盛器。靜嘉堂文庫美術館現藏一

罕例(圖一)。

為隆重其事,「口切之茶事」所用茶具均為名器,其「口覆」製作亦不惜工本,常以中國明代織錦精製而成。覆布與罐口之

間蓋紙數層,可保護纖細的珍貴布料。「口覆」本身貴為名物,早已價值不菲,與茶罐一併流傳,令本器更添歷史意義。

本罐每層覆布皆以不同絲料縫製,其中兩層施扁平金線緯織。

61