Page 14 - Sotheby's YAMANAK Vase Oct. 3, 2018

P. 14

A GLIMPSE OF THE PAST

SCREENED THROUGH THE PRESENT

REGINA KRAHL

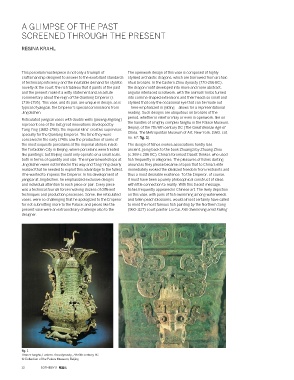

This porcelain masterpiece is not only a triumph of The openwork design of this vase is composed of highly

craftsmanship designed to answer to the exorbitant standards stylised archaistic dragons, which are borrowed from archaic

of technical proficiency and the insatiable demand for stylistic ritual bronzes. In the Eastern Zhou dynasty (770-256 BC),

novelty at the court; the rich tableau that it paints of the past the dragon motif developed into more and more abstract,

and the present make it a witty statement and an astute angular interlaced scrollwork, with the animals’ limbs turned

commentary about the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. into comma-shaped extensions and their heads so small and

1736-1795). This vase, and its pair, are unique in design, as is stylised that only the occasional eye that can be made out

typical of yangcai, the Emperor’s special commissions from – here emphasized in gilding – allows for a representational

Jingdezhen. reading. Such designs are ubiquitous on bronzes of the

period, whether in relief or inlay or even in openwork, like on

Reticulated yangcai vases with double walls (jiaceng linglong)

represent one of the last great innovations developed by the handles of a highly complex fanghu in the Palace Museum,

Tang Ying (1682-1756), the imperial kilns’ creative supervisor, Beijing, of the 7th/6th century BC (The Great Bronze Age of

specially for the Qianlong Emperor. The time they were China, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1980, cat.

conceived in the early 1740s saw the production of some of no. 67; fig. 1).

the most exquisite porcelains at the imperial ateliers inside The design of fishes evokes associations hardly less

the Forbidden City in Beijing, where porcelains were treated ancient, going back to the book Zhuangzi by Zhuang Zhou

like paintings; but Beijing could only operate on a small scale, (c.369-c.286 BC), China’s foremost Daoist thinker, who used

both in terms of quantity and size. The imperial workshops at fish frequently in allegories. The pleasures of fishes darting

Jingdezhen were not limited in this way and Tang Ying clearly around as they please became a topos that to China’s elite

realized that he needed to exploit this advantage to the fullest, immediately evoked the idealized freedom from restraints and

if he wanted to impress the Emperor. In his development of thus a most desirable existence. To the Emperor, of course,

yangcai at Jingdezhen, he emphasized exclusive designs it must have been a purely philosophical construct of ideas

and individual attention to each piece or pair. Every piece with little connection to reality. With this Daoist message,

was a technical tour de force involving dozens of different fishes frequently appeared in Chinese art. The lively depiction

techniques and production processes. Some, like reticulated on this vase, with pairs of fish swimming among waterweeds

vases, were so challenging that he apologized to the Emperor and fallen peach blossoms, would almost certainly have called

for not submitting more to the Palace; and pieces like the to mind the most famous fish painting by the Northern Song

present vase were an extraordinary challenge also to the (960-1127) court painter Liu Cai, Fish Swimming amid Falling

designer.

fig. 1

Bronze fanghu, Eastern Zhou dynasty, 7th-6th century BC

© Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

12 SOTHEBY’S 蘇富比