Page 407 - Edo: Art in Japan, 1615–1868

P. 407

220 222

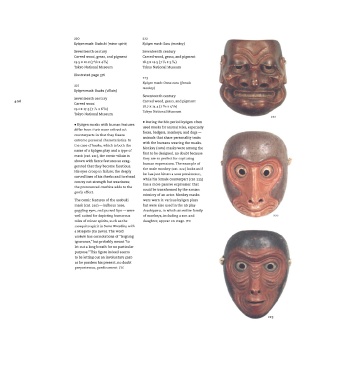

Kyogen mask: Usobuki (minor spirit) Kyogen mask: Saru (monkey)

Seventeenth century Seventeenth century

Carved wood, gesso, and pigment Carved wood, gesso, and pigment

3

5

3

19.5 X 12.2 (7 /8X4 A) 18.3x14.5 (7 74x5 / 4)

Tokyo National Museum Tokyo National Museum

Illustrated page 376

223

Kyogen mask: Onna zaru (female

221 monkey)

Kyogen mask: Buaku (uillain)

Seventeenth century

Seventeenth century

406 Carved wood, gesso, and pigment

Carved wood 18.7 x 14.4 (7 /sx 5 /s)

5

3

7

19.1 x 17.5 (772 x 6 /s) Tokyo National Museum

Tokyo National Museum

221

• During the Edo period kyógen often

• Kyogen masks with human features

differ from their more refined no used masks for animal roles, especially

counterparts in that they freeze foxes, badgers, monkeys, and dogs —

animals that share personality traits

extreme personal characteristics. In with the humans wearing the masks.

the case of buaku, which is both the

name of a kyógen play and a type of Monkey (saru) masks were among the

first to be designed, no doubt

because

mask (cat. 221), the comic villain is they are so perfect for capturing

shown with fierce features so exag-

gerated that they become facetious. human expressions. The example of

His eyes droop in failure; the deeply the male monkey (cat. 222) looks as if

he has just bitten

a sour persimmon,

carved lines of his cheeks and forehead while his female counterpart (cat. 223)

convey not strength but weariness; has a more passive expression that

the pronounced overbite adds to the could be transformed by the simian

goofy effect.

mimicry of an actor. Monkey masks

The comic features of the usobuki were worn in various kyógen plays

mask (cat. 220) — bulbous nose, but were also used in the no play

goggling eyes, and pursed lips — were Arashiyama, in which an entire family

well suited for depicting humorous of monkeys, including a son and

222

roles of minor spirits, such as the daughter, appear on stage. JTC

mosquito spirit in Sumo Wrestling with

a Mosquito (Ka zumo). The word

usobuki has connotations of "feigning

ignorance," but probably meant "to

let out a long breath for no particular

purpose." This figure indeed seems

to be letting out an involuntary gasp

as he ponders his present, no doubt

preposterous, predicament. JTC

223