Page 157 - japanese and korean art Utterberg Collection Christie's March 22 2022

P. 157

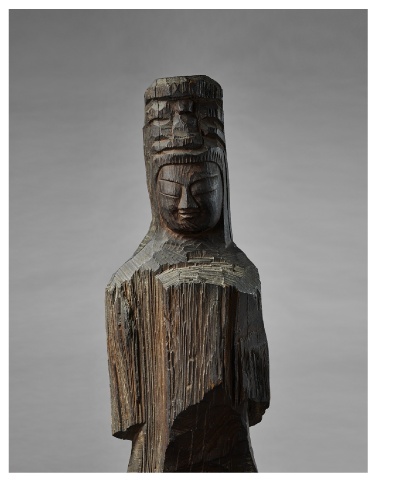

This sculpture is thought to date to the 1680s, when Enku was

in the Nikko area. The inscription in ink on the back, probably

not by Enku, is illegible except for a few words—clues to the

approximate date and the provenance: 元禄二年己巳六月十四日”

Genroku ninen tsuchinoto-mi rokugatsu nijuyokka (24 June 1689); 明覚

院 Myogaku-in.

The current owner’s grandfather, Yoshiara Yasuzo, was a member

of the Tochigi prefectural assembly in the small city of Nikko,

in the mountains north of Tokyo. Just before or after the war,

he was asked by the abbot of a local temple, the Myogaku-in, to

buy his temple’s main hall. Before the hall was moved to Yasuzo’s

garden, the abbot removed what he considered to be the important

Buddhist sculptures, but he left Enku’s Kannon, as Enku’s work

was not considered significant at that time. Today, there is no more

popular sculptor in Japan.

Yasuzo was at the center of the local cultural elite. He had

relationships with many individuals in the world of art and culture,

including the poet Takahama Kiyoshi; the painters Kosugi Hoan,

Ogawa Usen, Maruyama Banka and Nakamura Fusetsu; and the

poet and painter Shimizu Hian, at one time the mayor of Nikko.

Others who also visited and stayed at his home were the Kabuki

actors Nakamura Kichiemon; Nakamura Shikan; and Matsumoto

Koshiro. One visitor in the summer of 1961 was the famous potter

Hamada Shoji (shown with the Enku sculpture in the photo here),

a Living National Treasure, who worked in the pottery town of

Mashiko, also in Tochigi Prefecture (fig. 1). Hamada was a canny

collector of folk art and must have coveted this piece.

Enku was born into a poor family in Gifu Prefecture in the

early 17th century and left home as a boy to enter a local temple

affiliated with the Tendai sect. In his twenties, he learned the

rudiments of carving from itinerant woodworkers and began

traveling as an itinerant monk-sculptor, leaving behind thousands

of rough-hewn, powerful Buddhist images, many of which he

donated to local temples and the people who gave him shelter

along the way.

Fig.1 Photo of Yoshiara Yasuzo, Hamada Shoji and

the current lot (from left to right) at the home of

Yoshiara, 1961