Page 56 - Farm Bill Series_The 7 Things You Should Know

P. 56

But for cotton, where the U.S. has had such a small share of the market, a bad U.S. crop won’t be

much of a blip in global trading.

There are also a multitude of financial risks:

What if market prices skyrocket but a farmer

doesn’t have any crops or livestock to sell?

What if interest rates shoot up and he or she

can no longer repay loans on assets or

operating expenses? What if other countries

manipulate their currencies in a way that

make it more difficult to export U.S.

agricultural products?

And finally, one can’t rule out the political

risks that have battered farm incomes around

the globe over the years. What if the

president declares a grain embargo, as

President Jimmy Carter did in 1980 to

respond to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan? Grain prices plummeted as a result.

Almost two decades later, the Russian government shut off exports to the world in response to

drought and wildfires at home, sending commodity prices soaring.

As a result, “Wheat prices jumped over 7 percent in less than two months,” noted Stabenow in

her first official address as chairman of the Senate Agriculture Committee in January 2011.

“That’s why, as we look forward to writing the next farm bill, I am fully committed to a strong

safety net,” she told members attending the Michigan Agribusiness Council annual meeting in

2011.

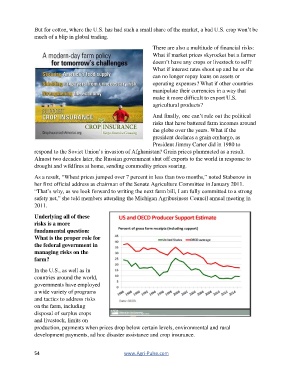

Underlying all of these

risks is a more

fundamental question:

What is the proper role for

the federal government in

managing risks on the

farm?

In the U.S., as well as in

countries around the world,

governments have employed

a wide variety of programs

and tactics to address risks

on the farm, including

disposal of surplus crops

and livestock, limits on

production, payments when prices drop below certain levels, environmental and rural

development payments, ad hoc disaster assistance and crop insurance.

54 www.Agri-Pulse.com