Page 6 - Demo

P. 6

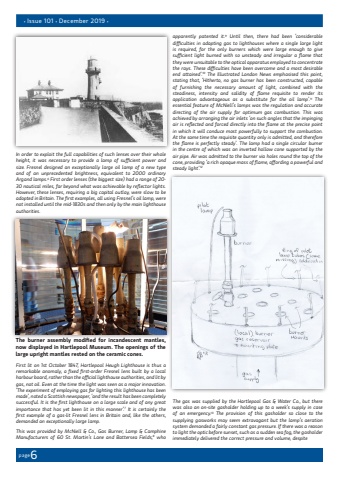

pagepage66%u2022 Issue 101 %u2022 December 2019 %u2022In order to exploit the full capabilities of such lenses over their whole height, it was necessary to provide a lamp of sufficient power and size. Fresnel designed an exceptionally large oil lamp of a new type and of an unprecedented brightness, equivalent to 2000 ordinary Argand lamps.6 First order lenses (the biggest size) had a range of 20-30 nautical miles, far beyond what was achievable by reflector lights. However, these lenses, requiring a big capital outlay, were slow to be adopted in Britain. The first examples, all using Fresnel%u2019s oil lamp, were not installed until the mid-1830s and then only by the main lighthouse authorities.First lit on 1st October 1847, Hartlepool Heugh Lighthouse is thus a remarkable anomaly, a fixed first-order Fresnel lens built by a local harbour board, rather than the official lighthouse authorities, and lit by gas, not oil. Even at the time the light was seen as a major innovation. %u2018The experiment of employing gas for lighting this lighthouse has been made%u2019, noted a Scottish newspaper, %u2018and the result has been completely successful. It is the first lighthouse on a large scale and of any great importance that has yet been lit in this manner%u2019.7 It is certainly the first example of a gas-lit Fresnel lens in Britain and, like the others, demanded an exceptionally large lamp.This was provided by McNiell & Co., Gas Burner, Lamp & Camphine Manufacturers of 60 St. Martin%u2019s Lane and Battersea Fields,8 who apparently patented it.9 Until then, there had been %u2018considerable difficulties in adapting gas to lighthouses where a single large light is required, for the only burners which were large enough to give sufficient light burned with so unsteady and irregular a flame that they were unsuitable to the optical apparatus employed to concentrate the rays. These difficulties have been overcome and a most desirable end attained%u2019.10 The Illustrated London News emphasised this point, stating that, %u2018Hitherto, no gas burner has been constructed, capable of furnishing the necessary amount of light, combined with the steadiness, intensity and solidity of flame requisite to render its application advantageous as a substitute for the oil lamp%u2019.11 The essential feature of McNiell%u2019s lamps was the regulation and accurate directing of the air supply for optimum gas combustion. This was achieved by arranging the air inlets %u2018on such angles that the impinging air is reflected and forced directly into the flame at the precise point in which it will conduce most powerfully to support the combustion. At the same time the requisite quantity only is admitted, and therefore the flame is perfectly steady%u2019. The lamp had a single circular burner in the centre of which was an inverted hollow cone supported by the air pipe. Air was admitted to the burner via holes round the top of the cone, providing %u2018a rich opaque mass of flame, affording a powerful and steady light%u2019.12The gas was supplied by the Hartlepool Gas & Water Co., but there was also an on-site gasholder holding up to a week%u2019s supply in case of an emergency.13 The provision of this gasholder so close to the supplying gasworks may seem extravagant but the lamp%u2019s aeration system demanded a fairly constant gas pressure. If there was a reason to light the optic before sunset, such as a sudden sea fog, the gasholder immediately delivered the correct pressure and volume, despite The burner assembly modified for incandescent mantles, now displayed in Hartlepool Museum. The openings of the large upright mantles rested on the ceramic cones.