Page 242 - Environment: The Science Behind the Stories

P. 242

Soil erosion is a global issue

In today’s world, people are the primary cause of erosion, and

we have accelerated it to unnaturally high rates. In a 2004

study, geologist Bruce Wilkinson analyzed prehistoric erosion

rates from the geologic record and compared these with mod-

ern rates. He concluded that human activities move over 10

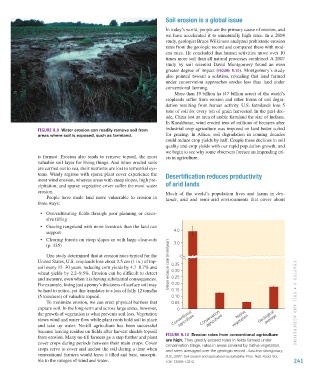

times more soil than all natural processes combined. A 2007

study by soil scientist David Montgomery found an even

greater degree of impact (Figure 9.10). Montgomery’s study

also pointed toward a solution, revealing that land farmed

under conservation approaches erodes less than land under

conventional farming.

More than 19 billion ha (47 billion acres) of the world’s

croplands suffer from erosion and other forms of soil degra-

dation resulting from human activity. U.S. farmlands lose 5

tons of soil for every ton of grain harvested. In the past dec-

ade, China lost an area of arable farmland the size of Indiana.

In Kazakhstan, wind eroded tens of millions of hectares after

Figure 9.9 Water erosion can readily remove soil from industrial crop agriculture was imposed on land better suited

areas where soil is exposed, such as farmland. for grazing. In Africa, soil degradation in coming decades

could reduce crop yields by half. Couple these declines in soil

quality and crop yields with our rapid population growth, and

we begin to see why some observers foresee an impending cri-

is formed. Erosion also tends to remove topsoil, the most sis in agriculture.

valuable soil layer for living things. And when eroded soils

are carried out to sea, their nutrients are lost to terrestrial sys-

tems. Windy regions with sparse plant cover experience the Desertification reduces productivity

most wind erosion, whereas areas with steep slopes, high pre-

cipitation, and sparse vegetative cover suffer the most water of arid lands

erosion. Much of the world’s population lives and farms in dry-

People have made land more vulnerable to erosion in lands, arid and semi-arid environments that cover about

three ways:

• Overcultivating fields through poor planning or exces-

sive tilling

• Grazing rangeland with more livestock than the land can

support 4.0

• Clearing forests on steep slopes or with large clear-cuts

(p. 335) 3.0

One study determined that at erosion rates typical for the

United States, U.S. croplands lose about 2.5 cm (1 in.) of top- 0.35

soil every 15–30 years, reducing corn yields by 4.7–8.7% and Mean erosion rate (mm/year)

wheat yields by 2.2–9.5%. Erosion can be difficult to detect 0.30

and measure, even when it is having substantial consequences. 0.25

For example, losing just a penny’s thickness of surface soil may 0.20

be hard to notice, yet this translates to a loss of fully 12 tons/ha 0.15

(5 tons/acre) of valuable topsoil. 0.10

To minimize erosion, we can erect physical barriers that 0.05 CHAPTER 9 • So I l AN d A gr I culT ure

capture soil. In the long-term and across large areas, however, 0

the growth of vegetation is what prevents soil loss. Vegetation Native Geological

agriculture

agriculture

slows wind and water flow while plant roots hold soil in place Conventional Conservation vegetation average

and take up water. No-till agriculture has been successful

because leaving residue on fields after harvest shields topsoil

from erosion. Many no-till farmers go a step further and plant Figure 9.10 Erosion rates from conventional agriculture

are high. They greatly exceed rates in fields farmed under

cover crops during periods between their main crops. Cover conservation tillage, rates in areas covered by native vegetation,

crops serve to cover and anchor the soil during a time when and rates averaged over the geologic record. Data from Montgomery,

conventional farmers would leave it tilled and bare, suscepti- D.R., 2007. Soil erosion and agricultural sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.

ble to the ravages of wind and water. 104: 13268–13272. 241

M09_WITH7428_05_SE_C09.indd 241 12/12/14 2:59 PM