Page 14 - Labatt BTRC Annual Report 2020-2021

P. 14

MEAGAN’S HUG

What Meagan’s HUG means to me – A scientist’s story

“10...9...8...”

A loudspeaker chanted out the countdown.

On either side of me, a chain of people holding hands snaked down the street encircling SickKids.

“4...3...”

Several of us momentarily broke the chain and waved back.

“2...1.”

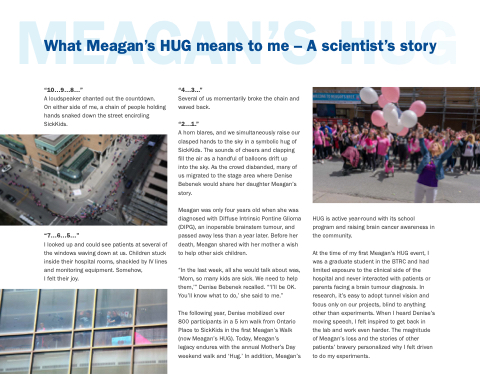

A horn blares, and we simultaneously raise our clasped hands to the sky in a symbolic hug of SickKids. The sounds of cheers and clapping fill the air as a handful of balloons drift up

into the sky. As the crowd disbanded, many of us migrated to the stage area where Denise Bebenek would share her daughter Meagan’s story.

Meagan was only four years old when she was diagnosed with Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG), an inoperable brainstem tumour, and passed away less than a year later. Before her death, Meagan shared with her mother a wish to help other sick children.

“In the last week, all she would talk about was, ‘Mom, so many kids are sick. We need to help them,’” Denise Bebenek recalled. “‘I’ll be OK. You’ll know what to do,’ she said to me.”

The following year, Denise mobilized over

800 participants in a 5 km walk from Ontario Place to SickKids in the first Meagan’s Walk (now Meagan’s HUG). Today, Meagan’s

legacy endures with the annual Mother’s Day weekend walk and ‘Hug.’ In addition, Meagan’s

“7...6...5...”

I looked up and could see patients at several of the windows waving down at us. Children stuck inside their hospital rooms, shackled by IV lines and monitoring equipment. Somehow,

I felt their joy.

HUG is active year-round with its school program and raising brain cancer awareness in the community.

At the time of my first Meagan’s HUG event, I was a graduate student in the BTRC and had limited exposure to the clinical side of the hospital and never interacted with patients or parents facing a brain tumour diagnosis. In research, it’s easy to adopt tunnel vision and focus only on our projects, blind to anything other than experiments. When I heard Denise’s moving speech, I felt inspired to get back in the lab and work even harder. The magnitude of Meagan’s loss and the stories of other patients’ bravery personalized why I felt driven to do my experiments.