Page 345 - J. C. Turner "History and Science of Knots"

P. 345

338 History and Science of Knots

usually undertook, macrame was the work that they would turn to. The re-

doubtable Dr. Samuel Johnson was not impressed by the ladies and their

fripperies; he said of them: `Knots ought to be reckoned in the scale of in-

significance as next to mere idleness.'

f..? is J. 1:: ^ a.:? t 11 11 f!

a..>< fit - :llc ' •a.:.r ,^ • •t. '.. ^...i• Y. ^ .Y ; t 0 ^:

R i ;^ s Vii'' S ?I s Y'.''^ i i iis

.a:t;Ct't't'!a't:lfaa'f't;t:ft't.^.ti:+t:t f:+j:^'t t't:1'.t'tsa;t:Ft;t.t.

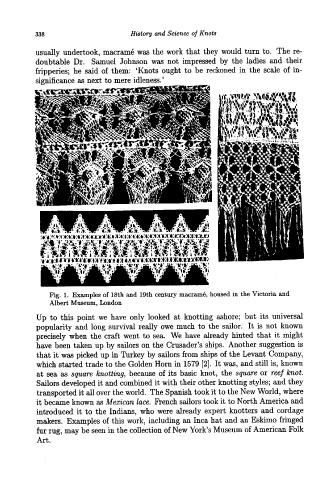

Fig. 1. Examples of 18th and 19th century macrame, housed in the Victoria and

Albert Museum, London

Up to this point we have only looked at knotting ashore; but its universal

popularity and long survival really owe much to the sailor. It is not known

precisely when the craft went to sea. We have already hinted that it might

have been taken up by sailors on the Crusader's ships. Another suggestion is

that it was picked up in Turkey by sailors from ships of the Levant Company,

which started trade to the Golden Horn in 1579 [2]. It was, and still is, known

at sea as square knotting, because of its basic knot, the square or reef knot.

Sailors developed it and combined it with their other knotting styles; and they

transported it all over the world. The Spanish took it to the New World, where

it became known as Mexican lace. French sailors took it to North America and

introduced it to the Indians, who were already expert knotters and cordage

makers. Examples of this work, including an Inca hat and an Eskimo fringed

fur rug, may be seen in the collection of New York's Museum of American Folk

Art.