Page 154 - J. C. Turner - History and Science of Knots

P. 154

144 History and Science of Knots

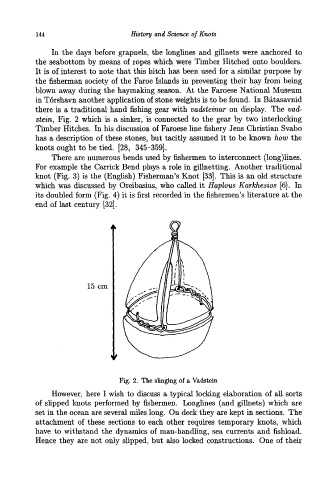

In the days before grapnels, the longlines and gillnets were anchored to

the seabottom by means of ropes which were Timber Hitched onto boulders.

It is of interest to note that this hitch has been used for a similar purpose by

the fisherman society of the Faroe Islands in preventing their hay from being

blown away during the haymaking season. At the Faroese National Museum

in Torshavn another application of stone weights is to be found. In Batasavnid

there is a traditional hand fishing gear with vadsteinur on display. The vad-

stein, Fig. 2 which is a sinker, is connected to the gear by two interlocking

Timber Hitches. In his discussion of Faroese line fishery Jens Christian Svabo

has a description of these stones, but tacitly assumed it to be known how the

knots ought to be tied. [28, 345-359].

There are numerous bends used by fishermen to interconnect (long)lines.

For example the Carrick Bend plays a role in gillnetting. Another traditional

knot (Fig. 3) is the (English) Fisherman's Knot [33]. This is an old structure

which was discussed by Oreibasius, who called it Haplous Karkhesios [6]. In

its doubled form (Fig. 4) it is first recorded in the fishermen's literature at the

end of last century [32].

A

15 cm

Fig. 2. The slinging of a Vadstein

However, here I wish to discuss a typical locking elaboration of all sorts

of slipped knots performed by fishermen. Longlines (and gillnets) which are

set in the ocean are several miles long. On deck they are kept in sections. The

attachment of these sections to each other requires temporary knots, which

have to withstand the dynamics of man-handling, sea currents and fishload.

Hence they are not only slipped, but also locked constructions. One of their