Page 113 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 113

PART one: MESOPOTAMIA

IS u Li U U ’Ll

m m

■ :1 i

^ nmm 1____

JP>

—

iil s::

S-=&wf I! W==i^=^^-^-* —> =_-.r£*- -r=

=^rn^m

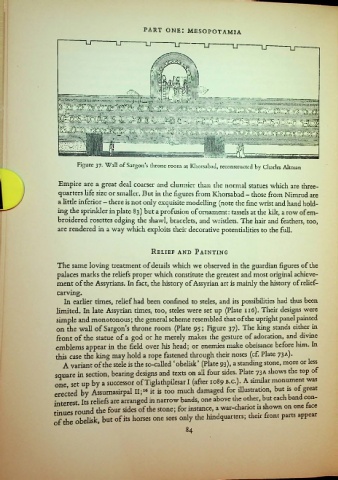

Figure 37. Wall of Sargon’s throne room at Khorsabad, reconstructed by Charles Altman

Empire are a great deal coarser and clumsier than the normal statues which are three-

quarters life size or smaller. But in the figures from Khorsabad - those from Nimrud are

a little inferior — there is not only exquisite modelling (note the fine wrist and hand hold

ing the sprinkler in plate 83) but a profusion of ornament: tassels at the kilt, a row of em

broidered rosettes edging the shawl, bracelets, and wristlets. The hair and feathers, too,

are rendered in a way which exploits their decorative potentialities to the full.

Relief and Painting

The same loving treatment of details which we observed in the guardian figures of the

palaces marks the reliefs proper which constitute the greatest and most original achieve

ment of the Assyrians. In fact, the history of Assyrian art is mainly the history of relief

carving.

In earlier times, relief had been confined to steles, and its possibilities had thus been

limited. In late Assyrian times, too, steles were set up (Plate 116). Their designs were

simple and monotonous; the general scheme resembled that of the upright panel painted

on the wall of Sargon’s throne room (Plate 95 ; Figure 37). The king stands either in

front of the statue of a god or he merely makes the gesture of adoration, and divine

emblems appear in the field over his head; or enemies make obeisance before him. In

this case the king may hold a rope fastened through their noses (cf. Plate 73A).

A variant of the stele is the so-called ‘obelisk* (Plate 93), a standing stone, more or less

square in section, bearing designs and texts on all four sides. Plate 73 a shows the top of

one, set up by a successor of Tiglathpilesar I (after 1089 b.c.). A similar monument was

erected by Assumasirpal II;16 it is too much damaged for illustration, but is of great

interest Its reliefs are arranged in narrow bands, one above the other, but each band con

tinues round the four sides of the stone; for instance, a war-chariot is shown on one face

of the obelisk, but of its horses one sees only the hindquarters; their front parts appear

84