Page 116 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 116

THE LATE ASSYRIAN PERIOD

Other scenes show Assurnasirpal’s bivouac, with his tent and the grooming of the un

harnessed horses;20 the army being ferried across a river, with the chariots mounted in

coracles (circular boats, the modern gufas of Iraq made of wattle and pitch), and the

horses, their bridles held by the men in the craft, swim the stream; foot-soldiers also

swim, sometimes assisted by floats of inflated skins.21 Elsewhere one sees the triumphant

return of the army; the chariotry with its standard, the infantry carrying cut-off heads,

while a vulture flies away with one of these trophies.22 Or one sees the king’s chariot

being led off the field.23 But in between these scenes appear the battles, the burning cities,

the unrelieved, sustained efficiency of Assyrian warfare.

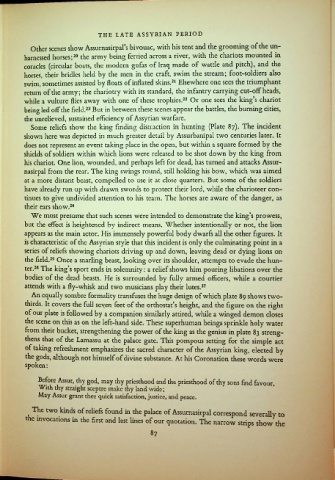

Some reliefs show the king finding distraction in hunting (Plate 87). The incident

shown here was depicted in much greater detail by Assurbanipal two centuries later. It

does not represent an event taking place in the open, but within a square formed by the

shields of soldiers within which lions were released to be shot down by the king from

his chariot. One lion, wounded, and perhaps left for dead, has turned and attacks Assur-

nasirpal from the rear. The king swings round, still holding his bow, which was aimed

at a more distant beast, compelled to use it at close quarters. But some of the soldiers

have already run up with drawn swords to protect their lord, wliile the charioteer con

tinues to give undivided attention to his team. The horses are aware of the danger, as

their ears show.24

We must presume that such scenes were intended to demonstrate the king’s prowess,

but the effect is heightened by indirect means. Whether intentionally or not, the lion

appears as the main actor. His immensely powerful body dwarfs all the other figures. It

is characteristic of the Assyrian style that this incident is only the culminating point in a

series of reliefs showing chariots driving up and down, leaving dead or dying lions on

the field.25 Once a snarling beast, looking over its shoulder, attempts to evade the hun

ter.26 The king’s sport ends in solemnity: a relief shows him pouring libations over the

bodies of the dead beasts. He is surrounded by fully armed officers, while a courtier

attends with a fly-whisk and two musicians play their lutes.27

An equally sombre formality transfuses the huge design of which plate 89 shows two-

thirds. It covers the full seven feet of the orthostat’s height, and the figure on the right

of our plate is followed by a companion similarly attired, wliile a winged demon closes

the scene on this as on the left-hand side. These superhuman beings sprinkle holy water

from their bucket, strengthening the power of the king as the genius in plate 83 streng

thens that of the Lamassu at the palace gate. This pompous setting for the simple act

of taking refreshment emphasizes the sacred character of the Assyrian king, elected by

the gods, although not himself of divine substance. At his Coronation these words were

spoken:

Before Assur, thy god, may thy priesthood and the priesthood of thy sons find favour,

With thy straight sceptre make thy land wide;

May Assur grant thee quick satisfaction, justice, and peacc.

The two kinds of reliefs found in the palace of Assumasirpal correspond severally to

the invocations in the first and last lines of our quotation. The narrow strips show the

87