Page 156 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 156

ASIA MINOR AND THE IIITTITES

Comparing the reliefs of the two galleries one may venture a guess as to the different

uses to which they were put. It has been suggested33 that the main gallery was used for

the swearing of state treaties and other functions which took place, before the thousand

gods of the realm of Hatti.34 The south gallery may have served for the installation of the

king or other rites of royalty.35 But these suggestions arc incapable of proof, since our

knowledge of Hittitc religion is still scanty.

The style of carving of the reliefs at Yasilikaya is similar to that used in the capital;

the rock carvings show the same heavy relief and truly plastic forms which we found in

the gate figures fromBoghazkcuy (Plates 125-8a).They corroborate our view that a dis

tinct school of sculpture existed in eastern Anatolia during the Hittitc empire. However,

its extant works arc few, and that perhaps not only as a result of destruction and loss. It

seems that the Hittitc sculptors were given much less scope than those of Egypt and

Mesopotamia. The Hittitc kings, great conquerors though they were, did not commis

sion pictorial records of their wars. Hittitc art was religious and the king, as we said, is

exclusively shown with the long priestly gown, the round cap and curved staff which

are attributes of his sacred office. He wears these even when he is depicted on the face of

the rocks in outlying or recently conquered parts of his realm, as at Sirkeli in Cilicia,36

or on orthostats as at Tell Atchana near Antioch 37 At Ala$a Hiiyiik,38 too, the king ap

pears in this garb on the orthostats which decorate the base of the tower protecting the

sphinx gate (Plate 12513). Inside the gate, on one of the door-jambs, appears the double-

headed eagle which is associated with two goddesses at Yasilikaya (Plate 130c) and

which, at Ala$a Hiiyiik, too, ‘supports’ a goddess (not a king, as has been said). The

eagle grasps an animal, probably a hare, in either claw forming a group which was popu

lar in Mesopotamia in Early Dynastic times (Plates 27A and 32) although the double

headed eagle only appears there with the Third Dynasty of Ur.39 The orthostats are

covered with elaborate scenes, but they are poorly cut; they entirely lack the corporeal

ity which the thorough modelling imparted to the figures at Boghazkeuy and Yasili

kaya. At Ala^a Hiiyiik the figures are merely outlined and stand quite flat above the

background, which has been chiselled down. The details arc rendered by engraved lines,

not by modelling. Each orthostat is treated as a whole to the extent that figures do not

overlap their edges, but a single scene may

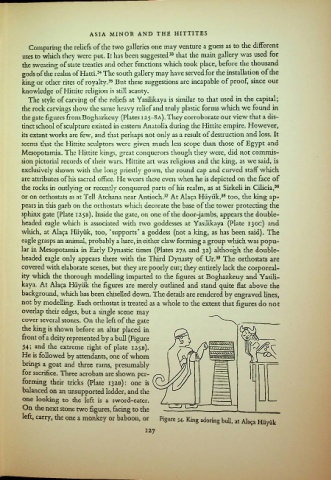

cover several stones. On the left of the gate

the king is shown before an altar placed in

front of a deity represented by a bull (Figure

V\\\ WWW V

54; and the extreme right of plate 125B).

He is followed by attendants, one of whom

brings a goat and three rams, presumably

for sacrifice. Three acrobats are shown per

forming their tricks (Plate 132B): one is

balanced on an unsupported ladder, and the

one looking to the left is a sword-eater.

On the next stone two figures, facing to the

left, carry, the one a monkey or baboon, or

Figure 54. King adoring bull, at A^a Hiiyiik

127