Page 240 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 240

THE ART OF ANCIENT PERSIA

hind legs, upside down, within a surround shaped like goats’ necks with heads flanking

the hero’s face. In figure 105 nothing remains of him but his head, jutting out from the

lion’s joined paws, and his girdle, joining - incongruously but beautifully - the two great

beasts. In plate 176c lie is better preserved, but duplicated, and the effect recalls totem

poles. The old theme served in Luristan as a starting-point for all kinds of fascinating in

ventions, wliilc the original meaning is lost sight of. For the hero between beasts, like all

symmetrical motifs, carried in itself a balanced harmony which would appeal to decora

tors. The group, like the pairs of antithetical animals (Plate 177c), was, for instance, highly

eff ective as the finial of the four poles of the funerary car on which a chief was buried.36

The composition of such splendid pieces need not be questioned too closely. In plate

176c one may doubt whether the lower part belongs to the ‘man’ in front view or

renders the hindquarters of two animals. But this is quite unimportant; what matters in

all these pole-tops is the dashing outline; the rich play of light over the varied forms;

the surprising suggestion, in many places, of life breaking forth. In the ‘totem-pole’ de

signs that is obvious, but in plate 177c the volutes enriching the main theme - two ibexes

include two small animals; and in plate 177A two goats’ heads emerge from the front

paws of the beasts, and their rumps have been replaced by two small lions. The pins

(Plate 176, A and b) achieve similar effects within a closed outline and the check-pieces

repeat them; in one (Figure 104E) the top of a monster’s wing lives as a bull, the hind

quarters of a moufflon exist as a horned demon (Figure 104F). Belt-buckles, bracelets, and

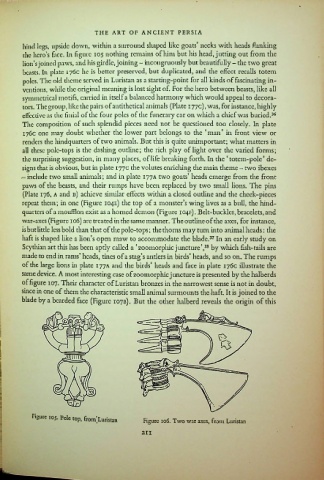

war-axes (Figure 106) are treated in the same manner. The outline of the axes, for instance,

is but little less bold than that of the pole-tops; the thorns may turn into animal heads: the

haft is shaped like a lion’s open maw to accommodate the blade.37 In an early study on

Scythian art this has been aptly called a ‘zoomorpliic juncture’,38 by which fish-tails are

made to end in rams’ heads, tines of a stag’s antlers in birds’ heads, and so on. The rumps

of the large lions in plate 177A and the birds’ heads and face in plate 176c illustrate the

same device. A most interesting case of zoomorphic juncture is presented by the halberds

of figure 107. Then* character of Luristan bronzes in the narrowest sense is not in doubt,

since in one of them the characteristic small animal surmounts the haft. It is joined to the

blade by a bearded face (Figure 107B). But the other halberd reveals the origin of this

Figure 105. Pole top, from’Luristan

Figure 106. Two war axes, from Luristan

211