Page 241 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 241

PART two: the peripheral

regions

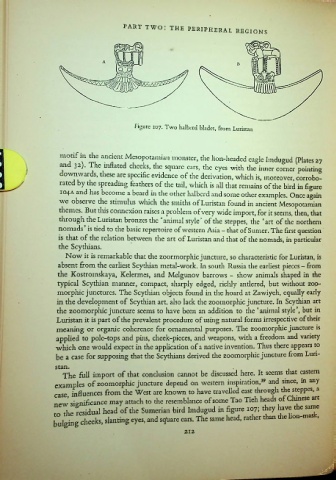

Figure 107. Two halberd blades, frona Luristan

motif in the ancient Mesopotamian monster, the lion-headed eagle Imdugud (Plates 27

and 32). The inflated cheeks, the square cars, the eyes with the inner corner pointing

downwards, these are specific evidence of the derivation, which is, moreover, corrobo

rated by the spreading feathers of the tail, which is all that remains of the bird in figure

104A and has become a beard in the other halberd and some other examples. Once again

we observe the stimulus which die smiths of Luristan found in ancient Mesopotamian

themes. But this connexion raises a problem of very wide import, for it seems, then, that

through the Luristan bronzes die ‘animal style’ of the steppes, the ‘art of the northern

nomads is tied to the basic repertoire of western Asia - that of Sumer. The first question

is that of the relation between the art of Luristan and that of the nomads, in particular

the Scythians.

Now it is remarkable that the zoormorphic juncture, so characteristic for Luristan, is

absent from the earliest Scythian metal-work. In south Russia the earliest pieces - from

the Kostromskaya, Kelermes, and Melgunov barrows - show animals shaped in the

typical Scythian manner, compact, sharply edged, richly andered, but without zoo-

morphic junctures. The Scythian objects found in the hoard at Zawiyeh, equally early

in the development of Scythian art, also lack the zoomorphic juncture. In Scythian art

the zoomorphic juncture seems to have been an addition to the ‘animal style’, but in

Luristan it is part of the prevalent procedure of using natural forms irrespective of their

meaning or organic coherence for ornamental purposes. The zoomorphic juncture is

applied to pole-tops and pins, cheek-pieces, and weapons, with a freedom and variety

which one would expect in the application of a native invention. Thus there appears to

be a case for supposing that the Scythians derived the zoomorphic juncture from Lun-

stan.

The full import of that conclusion cannot be discussed here. It seems that eastern

examples of zoomorphic juncture depend on western inspiration,39 and since, in any

case influences from the West are known to have travelled east through the steppes, a

new significance may attach to the resemblance of some Tao Tieh heads of Chinese art

m the residual head of the Sumerian bird Imdugud in figure 107; they have t e same

bulging checks, slanting eyes, and square ears. The same head, rather than die on-mas',

212

A