Page 84 - The Art & Architecture of the Ancient Orient_Neat

P. 84

THE ISIN-LARSA PERIOD

north end; but the effect of the piers is here clearly that of a separation between a broad

but shallow cclla and a long antccclla. The next step could be either an adaptation of the

antecella t0 the shape of the cella or the substitution of an open court for the antccella.

Both alternatives appear in figure 19.1 emphasize these details of the plans because far-

reaching conclusions have been based on differences in temple plans. Distinct ethnic

groups have been proclaimed the builders of temples which, however different they may

appear, can now be understood as successive stages in a continuous architectural develop-

ment.21

10 METRES

FEET

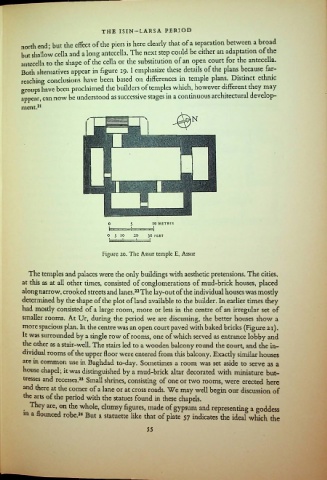

Figure 20. The Assur temple E, Assur

The temples and palaces were the only buildings with aesthetic pretensions. The cities,

at tliis as at all other times, consisted of conglomerations of mud-brick houses, placed

along narrow, crooked streets and lanes.22 The lay-out of the individual houses was mostly

determined by the shape of the plot of land available to the builder. In earlier times they

had mostly consisted of a large room, more or less in the centre of an irregular set of

smaller rooms. At Ur, during the period we are discussing, the better houses show a

more spacious plan. In the centre was an open court paved with baked bricks (Figure 21).

It was surrounded by a single row of rooms, one of which served as entrance lobby and

the other as a stair-well. The stairs led to a wooden balcony round the court, and the in

dividual rooms of the upper floor were entered from this balcony. Exactly similar houses

are in common use in Baghdad to-day. Sometimes a room was set aside to serve as a

house chapel; it was distinguished by a mud-brick altar decorated with miniature but

tresses and recesses.23 Small shrines, consisting of one or two rooms, were erected here

and there at the corner of a lane or at cross roads. We may well begin our discussion of

the arts of the period with the statues found in these chapels.

They are, on the whole, clumsy figures, made of gypsum and representing a goddess

111 a flounced robe.24 But a statuette like that of plate 57 indicates the ideal which the

55