Page 151 - The Arabian Gulf States_Neat

P. 151

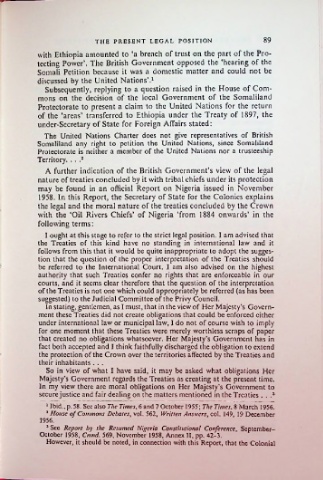

THE PRESENT LEGAL POSITION 89

with Ethiopia amounted to ‘a breach of trust on the part of the Pro

tecting Power’. The British Government opposed the ‘hearing of the

Somali Petition because it was a domestic matter and could not be

discussed by the United Nations’.1

Subsequently, replying to a question raised in the House of Com-

mons on the decision of the local Government of the Somaliland

Protectorate to present a claim to the United Nations for the return

of the ‘areas’ transferred to Ethiopia under the Treaty of 1897, the

undcr-Sccretary of State for Foreign AfTairs stated:

The United Nations Charter docs not give representatives of British

Somaliland any right to petition the United Nations, since Somaliland

Protectorate is neither a member of the United Nations nor a trusteeship

Territory. . . .2

A further indication of the British Government’s view of the legal

nature of treaties concluded by it with tribal chiefs under its protection

may be found in an official Report on Nigeria issued in November

1958. In this Report, the Secretary of State for the Colonics explains

the legal and the moral nature of the treaties concluded by the Crown

with the ‘Oil Rivers Chiefs’ of Nigeria ‘from 1884 onwards’ in the

following terms:

I ought at this stage to refer to the strict legal position. I am advised that

the Treaties of this kind have no standing in international law and it

follows from this that it would be quite inappropriate to adopt the sugges

tion that the question of the proper interpretation of the Treaties should

be referred to the International Court. I am also advised on the highest

authority that such Treaties confer no rights that are enforceable in our

courts, and it seems clear therefore that the question of the interpretation

of the Treaties is not one which could appropriately be referred (as has been

suggested) to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

In stating, gentlemen, as I must, that in the view of Her Majesty’s Govern

ment these Treaties did not create obligations that could be enforced cither

under international law or municipal law, I do not of course wish to imply

for one moment that these Treaties were merely worthless scraps of paper

that created no obligations whatsoever. Her Majesty’s Government has in

fact both accepted and I think faithfully discharged the obligation to extend

the protection of the Crown over the territories affected by the Treaties and

their inhabitants . . .

So in view of what I have said, it may be asked what obligations Her

Majesty’s Government regards the Treaties as creating at the present time.

In my view there arc moral obligations on Her Majesty’s Government to

secure justice and fair dealing on the matters mentioned in the Treaties . . .3

1 Ibid., p. 58. See also The Times, 6 and 7 October 1955; The Times, 8 March 1956.

2 House of Commons Debates, vol. 562, Written Answers, col. 149, 19 December

1956.

3 See Report by the Resumed Nigeria Constitutional Conference, Scptcmber-

October 1958, Cmnd. 569, November 1958, Annex II, pp. 42-3.

However, it should be noted, in connection with this Report, that the Colonial

I