Page 262 - Art In The Age Of Exploration (Great Section on Chinese Art Ming Dynasty)

P. 262

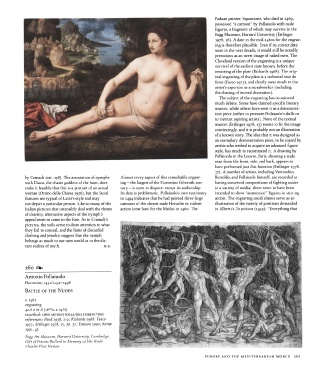

Paduan painter, Squarcione, who died in 1469,

possessed "a cartoon" by Pollaiuolo with nude

figures, a fragment of which may survive in the

Fogg Museum, Harvard University (Ettlinger

1978, 36). A date in the mid-i46os for the engrav-

ing is therefore plausible. Even if its correct date

were in the next decade, it would still be notably

precocious as an overt image of naked men. The

Cleveland version of the engraving is a unique

survival of the earliest state known, before the

recutting of the plate (Richards 1968). The orig-

inal engraving of the plate is a technical tour de

force (Fusco 1973), and clearly owes much to the

artist's expertise as a metalworker (including

the chasing of incised decoration).

The subject of the engraving has occasioned

much debate. Some have claimed specific literary

sources, while others have seen it as a demonstra-

tion piece (either to promote Pollaiuolo's skills or

to instruct aspiring artists). None of the textual

sources (Ettlinger 1978,15) seems to fit the image

convincingly, and it is probably not an illustration

of a known story. The idea that it was designed as

an exemplary demonstration piece, to be copied by

artists who wished to acquire an advanced figure

style, has much to recommend it. A drawing by

Pollaiuolo in the Louvre, Paris, showing a nude

man from the front, side, and back, appears to

have performed just this function (Ettlinger 1978,

37). A number of artists, including Verrocchio,

by Cranach (cat. 158). The association of nymphs Almost every aspect of this remarkable engrav- Bertoldo, and Pollaiuolo himself, are recorded as

with Diana, the chaste goddess of the hunt, does ing—the largest of the Florentine fifteenth cen- having conceived compositions of fighting nudes

make it feasible that this is a portrait of an actual tury— is open to dispute, except its authorship. in a variety of media; these seem to have been

woman (Ottino della Chiesa 1956), but the facial Its date is problematic. Pollaiuolo's own testimony intended to show "anatomical" figures in stirring

features are typical of Luini's style and may in 1494 indicates that he had painted three large action. The engraving could almost serve as an

not depict a particular person. Like so many of the canvases of the almost nude Hercules in violent illustration of the variety of positions demanded

Italian pictures that ostensibly deal with the theme action (now lost) for the Medici in 1460. The in Alberti's De pictura (1435): "Everything that

of chastity, alternative aspects of the nymph's

appeal seem to come to the fore. As in Cranach's

pictures, the veils serve to draw attention to what

they fail to conceal, and the hints of discarded

clothing and jewelry suggest that the nymph

belongs as much to our own world as to the dis-

tant realms of myth. M.K.

i6o

Antonio Pollaiuolo

Florentine, 1431/1432-1498

BATTLE OF THE NUDES

c. 1465

engraving

11

1

42.8x6i.8(i6 /i6X24 /

inscribed: OPVS ANTONII POLLA/IOLI HORENT/TINI

references: Hind 1938, 1:9; Richards 1968; Fusco

1973; Ettlinger 1978, 15, 36, 37; Emison 1990; Kemp

1

Z99 / 43

Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge,

Gift of Francis Bullard in Memory of His Uncle

Charles Eliot Norton

EUROPE AND THE MEDITERRANEAN WORLD 261