Page 264 - Art In The Age Of Exploration (Great Section on Chinese Art Ming Dynasty)

P. 264

162

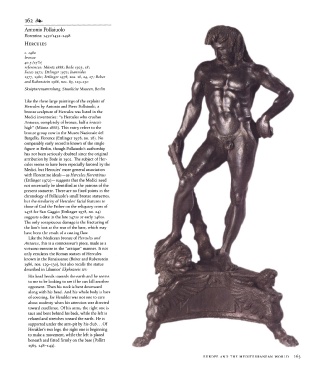

Antonio Pollaiuolo

Florentine, 1431/1432-1498

HERCULES

c. 1480

bronze

7

40.5 fi5 /sj

references: Muntz 1888; Bode 1923, 18;

Fusco 1971; Ettlinger 1972; Joannides

1977,1981; Ettlinger 1978, nos. 18, 24, 27; Bober

and Rubenstein 1986, nos. 89, 129-130

Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Museen, Berlin

Like the three large paintings of the exploits of

Hercules by Antonio and Piero Pollaiuolo, a

bronze sculpture of Hercules was listed in the

Medici inventories: "a Hercules who crushes

Antaeus, completely of bronze, half a braccio

high' 7 (Miintz 1888). This entry refers to the

bronze group now in the Museo Nazionale del

Bargello, Florence (Ettlinger 1978, no. 18). No

comparably early record is known of the single

figure in Berlin, though Pollaiuolo's authorship

has not been seriously doubted since the original

attribution by Bode in 1902. The subject of Her-

cules seems to have been especially favored by the

Medici, but Hercules' more general association

with Florentine ideals — as Hercules florentinus

(Ettlinger 1972) — suggests that the Medici need

not necessarily be identified as the patrons of the

present statuette. There are no fixed points in the

chronology of Pollaiuolo's small bronze statuettes,

but the similarity of Hercules' facial features to

those of God the Father on the reliquary cross of

1478 for San Gaggio (Ettlinger 1978, no. 24)

suggests a date in the late 14705 or early 14805.

The only conspicuous damage is the fracturing of

the lion's foot at the rear of the base, which may

have been the result of a casting flaw.

Like the Medicean bronze of Hercules and

Antaeus, this is a connoisseur's piece, made as a

virtuoso exercise in the "antique" manner. It not

only emulates the Roman statues of Hercules

known in the Renaissance (Bober and Rubenstein

1986, nos. 129-130), but also recalls the statue

described in Libanios' Ekphraseis xv:

His head bends towards the earth and he seems

to me to be looking to see if he can kill another

opponent. Then his neck is bent downward

along with his head. And his whole body is bare

of covering, for Herakles was not one to care

about modesty when his attention was directed

toward excellence. Of his arms, the right one is

taut and bent behind his back, while the left is

relaxed and stretches toward the earth. He is

supported under the arm-pit by his club... Of

Herakles's two legs, the right one is beginning

to make a movement, while the left is placed

beneath and fitted firmly on the base (Pollitt

1965,148-149).

EUROPE AND THE MEDITERRANEAN WORLD 263