Page 494 - Art In The Age Of Exploration (Great Section on Chinese Art Ming Dynasty)

P. 494

work, they scarcely attempted to represent moods

by inventing gloomy palettes for tragedies or jolly

ones for marriages.

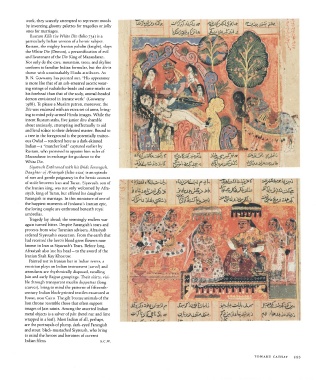

Rustam Kills the White Div (folio /3a) is a

particularly Indian version of a heroic subject.

Rustam, the mighty Iranian paladin (knight), slays

the White Div (Demon), a personification of evil

and lieutenant of the Div King of Mazandaran.

Not only do the cave, mountain, trees, and skyline

conform to familiar Indian formulas, but the div is

shown with unmistakably Hindu attributes. As

B. N. Goswamy has pointed out, "His appearance

is more like that of an ash-smeared ascetic wear-

ing strings of rudraksha-beads and caste marks on

his forehead than that of the scaly, animal-headed

demon envisioned in Iranate work" (Goswamy

1988). To please a Muslim patron, moreover, the

Div was endowed with an extra set of arms, bring-

ing to mind poly-armed Hindu images. While the

intent Rustam stabs, five junior divs shamble

about anxiously, attempting ineffectually to aid

and lend solace to their defeated master. Bound to

a tree in the foreground is the potentially traitor-

ous Owlad —rendered here as a dark-skinned

Indian —a "marcher lord" captured earlier by

Rustam, who promised to appoint him ruler of

Mazandaran in exchange for guidance to the

White Div.

Siyavush Enthroned with his Bride Farangish,

Daughter of Afrasiyab (folio ii2a) is an episode

of rare and gentle poignancy in the heroic account

of strife between Iran and Turan. Siyavush, son of

the Iranian king, was not only welcomed by Afra-

siyab, king of Turan, but offered his daughter

Farangish in marriage. In this miniature of one of

the happiest moments of Firdawsi's Iranian epic,

the loving couple are enthroned beneath royal

umbrellas.

Tragedy lay ahead; the seemingly endless war

again turned bitter. Despite Farangish/s tears and

protests from wise Turanian advisers, Afrasiyab

ordered Siyavush's execution. From the earth that

had received the hero's blood grew flowers now

known in Iran as Siyavush's Tears. Before long,

Afrasiyab also lost his head —to the sword of the

Iranian Shah Kay Khosrow.

Painted not in Iranian but in Indian terms, a

musician plays an Indian instrument (sarod) and

attendants are rhythmically disposed, recalling

Jain and early Rajput groupings. Their skirts, visi-

ble through transparent muslin duppattas (long

scarves), bring to mind the patterns of fifteenth-

century Indian block-printed textiles excavated at

Fostat, near Cairo. The gilt bronze animals of the

lion throne resemble those that often support

images of Jain saints. Among the assorted Indian

metal objects is a salver of pan (betel nut and lime

wrapped in a leaf). Most Indian of all, perhaps,

are the portrayals of plump, dark-eyed Farangish

and stout, black-mustached Siyavush, who bring

to mind the heroes and heroines of current

Indian films. s.c.w.

TOWARD CATHAY 493