Page 306 - Magistrates Conference 2019

P. 306

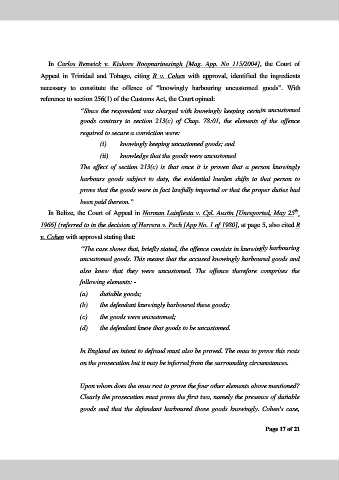

In Carlos Renwick v. Kishore Roopnarinesingh [Mag. App. No 115/2004], the Court of

Appeal in Trinidad and Tobago, citing R v. Cohen with approval, identified the ingredients

necessary to constitute the offence of “knowingly harbouring uncustomed goods”. With

reference to section 256(1) of the Customs Act, the Court opined:

“Since the respondent was charged with knowingly keeping certain uncustomed

goods contrary to section 213(c) of Chap. 78:01, the elements of the offence

required to secure a conviction were:

(i) knowingly keeping uncustomed goods; and

(ii) knowledge that the goods were uncustomed

The effect of section 213(c) is that once it is proven that a person knowingly

harbours goods subject to duty, the evidential burden shifts to that person to

prove that the goods were in fact lawfully imported or that the proper duties had

been paid thereon.”

th

In Belize, the Court of Appeal in Norman Lainfiesta v. Cpl. Austin [Unreported, May 25 ,

1966] (referred to in the decision of Herrera v. Pech [App No. 1 of 1980], at page 5, also cited R

v. Cohen with approval stating that:

“The case shows that, briefly stated, the offence consists in knowingly harbouring

uncustomed goods. This means that the accused knowingly harboured goods and

also knew that they were uncustomed. The offence therefore comprises the

following elements: -

(a) dutiable goods;

(b) the defendant knowingly harboured these goods;

(c) the goods were uncustomed;

(d) the defendant knew that goods to be uncustomed.

In England an intent to defraud must also be proved. The onus to prove this rests

on the prosecution but it may be inferred from the surrounding circumstances.

Upon whom does the onus rest to prove the four other elements above mentioned?

Clearly the prosecution must prove the first two, namely the presence of dutiable

goods and that the defendant harboured those goods knowingly. Cohen's case,

Page 17 of 21