Page 33 - All About History 55 - 2017 UK

P. 33

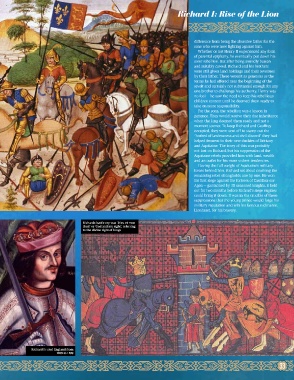

Richard I: Rise of the Lion

difference from being the absentee father for the

sons who were now fighting against him.

Whether or not Henry II experienced any form

of parental epiphany, he eventually put down his

sons’ rebellion. But after being soundly beaten

and suitably cowed, Richard and his brothers

were still given land holdings and their revenues

by their father. These weren’t as generous as the

terms he had offered near the beginning of the

revolt and certainly not substantial enough for any

one brother to challenge his authority. Henry was

no fool — he saw the need to keep his rebellious

children content until he deemed them ready to

take on more responsibility.

For the sons, the rebellion was a lesson in

patience. They would receive their due inheritance

when the king deemed them ready and not a

moment sooner. To keep Richard and Geoffrey

occupied, they were sent off to stamp out the

“hotbed of lawlessness and civil discord” they had

helped ferment in their new duchies of Brittany

and Aquitaine. The irony of this was probably

not lost on Richard, but his suppression of the

Aquitaine rebels provided him with land, wealth

and an outlet for his more violent tendencies.

Having the full weight of Aquitaine’s military

forces behind him, Richard set about crushing the

remaining rebel strongholds one by one. He won

his first siege against the fortress of Castillon-sur-

Agen — garrisoned by 30 seasoned knights, it held

out for two months before Richard’s siege engines

could bring it down. It was in the crucible of these

suppressions that the young prince would forge his

military reputation and win his famous nickname,

Lionheart, for his bravery.

Richards battle cry was ‘Dieu et mon

droit’ or ‘God and my right’, referring

to the divine right of kings

Richard I ruled England from

1189 to 1199

33