Page 260 - [Uma_Sekaran]_Research_methods_for_business__a_sk(BookZZ.org)

P. 260

244 DATA COLLECTION METHODS

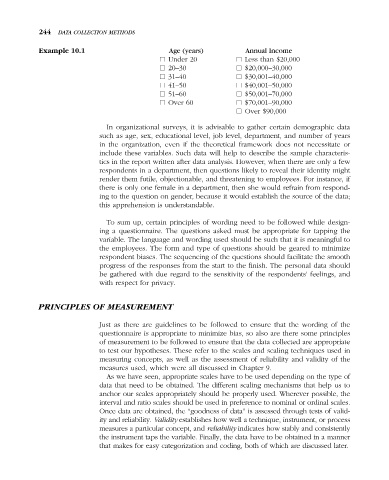

Example 10.1 Age (years) Annual Income

Under 20 Less than $20,000

20–30 $20,000–30,000

31–40 $30,001–40,000

41–50 $40,001–50,000

51–60 $50,001–70,000

Over 60 $70,001–90,000

Over $90,000

In organizational surveys, it is advisable to gather certain demographic data

such as age, sex, educational level, job level, department, and number of years

in the organization, even if the theoretical framework does not necessitate or

include these variables. Such data will help to describe the sample characteris-

tics in the report written after data analysis. However, when there are only a few

respondents in a department, then questions likely to reveal their identity might

render them futile, objectionable, and threatening to employees. For instance, if

there is only one female in a department, then she would refrain from respond-

ing to the question on gender, because it would establish the source of the data;

this apprehension is understandable.

To sum up, certain principles of wording need to be followed while design-

ing a questionnaire. The questions asked must be appropriate for tapping the

variable. The language and wording used should be such that it is meaningful to

the employees. The form and type of questions should be geared to minimize

respondent biases. The sequencing of the questions should facilitate the smooth

progress of the responses from the start to the finish. The personal data should

be gathered with due regard to the sensitivity of the respondents’ feelings, and

with respect for privacy.

PRINCIPLES OF MEASUREMENT

Just as there are guidelines to be followed to ensure that the wording of the

questionnaire is appropriate to minimize bias, so also are there some principles

of measurement to be followed to ensure that the data collected are appropriate

to test our hypotheses. These refer to the scales and scaling techniques used in

measuring concepts, as well as the assessment of reliability and validity of the

measures used, which were all discussed in Chapter 9.

As we have seen, appropriate scales have to be used depending on the type of

data that need to be obtained. The different scaling mechanisms that help us to

anchor our scales appropriately should be properly used. Wherever possible, the

interval and ratio scales should be used in preference to nominal or ordinal scales.

Once data are obtained, the “goodness of data” is assessed through tests of valid-

ity and reliability. Validity establishes how well a technique, instrument, or process

measures a particular concept, and reliability indicates how stably and consistently

the instrument taps the variable. Finally, the data have to be obtained in a manner

that makes for easy categorization and coding, both of which are discussed later.