Page 308 - Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Coverage Book 2023-24

P. 308

opus numbers, but Shirinyan binds them together thoughtfully, the fourth representing something

of a relaxation after the fire of the first three, the severe technical difficulties worn lightly.

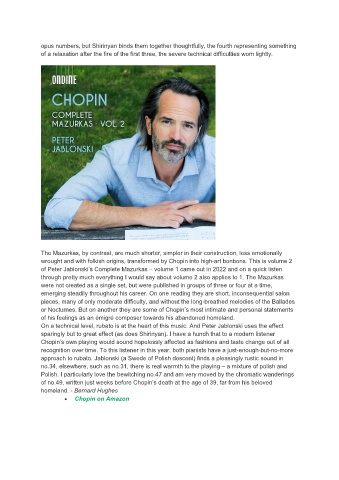

The Mazurkas, by contrast, are much shorter, simpler in their construction, less emotionally

wrought and with folkish origins, transformed by Chopin into high-art bonbons. This is volume 2

of Peter Jablonski’s Complete Mazurkas – volume 1 came out in 2022 and on a quick listen

through pretty much everything I would say about volume 2 also applies to 1. The Mazurkas

were not created as a single set, but were published in groups of three or four at a time,

emerging steadily throughout his career. On one reading they are short, inconsequential salon

pieces, many of only moderate difficulty, and without the long-breathed melodies of the Ballades

or Nocturnes. But on another they are some of Chopin’s most intimate and personal statements

of his feelings as an émigré composer towards his abandoned homeland.

On a technical level, rubato is at the heart of this music. And Peter Jablonski uses the effect

sparingly but to great effect (as does Shirinyan). I have a hunch that to a modern listener

Chopin’s own playing would sound hopelessly affected as fashions and taste change out of all

recognition over time. To this listener in this year, both pianists have a just-enough-but-no-more

approach to rubato. Jablonski (a Swede of Polish descent) finds a pleasingly rustic sound in

no.34, elsewhere, such as no.31, there is real warmth to the playing – a mixture of polish and

Polish. I particularly love the bewitching no.47 and am very moved by the chromatic wanderings

of no.49, written just weeks before Chopin’s death at the age of 39, far from his beloved

homeland. - Bernard Hughes

• Chopin on Amazon