Page 12 - EUREKA Winter 2017

P. 12

Artisanal bread is baking, fermented kombucha tea is being

bottled and fresh coffee beans are spilling from the roaster

with the rat-tat-tat of a hailstorm on a tin roof. All of this

is a backdrop to a stream of laptop-toting students and

shivering construction workers stopping in to caffeinate at

the café that fronts Bridgehead’s roastery on Preston Street

in Ottawa’s Little Italy.

In the glass-walled “Coffee lab” at the back of the If you look at this Rwanda, which is rich and toffee-like and

14,000-square-foot retail and industrial space, a pair of caramel-y right now, in 12 months it’s guaranteed that the

bearded sneaker-wearing coffee connoisseurs are measur- same coffee will taste like stale branches and cereal.”

ing out a morning cup. Or rather, 15. Neither Clark nor Hansen knows when that change will oc-

Ian Clark and Cliff Hansen are cupping, a quality grad- cur. No one does. Coffee from the same region — even the

ing process in which trained tasters slurp teaspoon-sized same farm — ages differently. Different lots from the same

samples of fine coffees to evaluate characteristics such as shipment can turn stale at different times.

acidity, aroma and body. Clark is the director of coffee at the It’s a persistent problem that shows up not only in the

Ottawa-based chain; Hansen is their head roaster. Founded taste of a cup of java, but also on the bottom line. Bridge-

in 1981 by United Church ministers concerned about the ex- head pays up to four times the standard price for the finest

ploitation of small-scale Nicaraguan coffee farmers, Bridge- beans, and when an exceptional coffee fades, its price point

head became the first company in Canada to sell fairly does likewise.

Coffee from the same region — even the same farm — ages

differently. It’s a persistent problem that shows up not only in the taste

of a cup of java, but on the bottom line.

traded coffee. It was acquired by Oxfam Canada and turned

into a for-profit company, and in 1999 was sold to Ottawa’s

Tracey Clark. Today, there are 20 locations across the city.

From the moment that Ian Clark and Hansen speak, it’s

clear this isn’t their first coffee of the day. “In a sense, cup-

ping is inherently subjective because it’s my perception of the

coffee,” Clark (no relation to Tracey) says in the accelerated

staccato of the over-caffeinated. “There is a pretty good level

of calibration around what the different scores mean in cup-

ping, but the subjective ultimately is what matters, because

the coffee is also being perceived by the customer.”

Still, there are unknowns. Each of the 15 cups represents

8,000 pounds of newly landed coffee beans. Five from

Colombia. Five from Rwanda. Five from Congo. All smell

delectable — for now.

“Aroma is the most relevant characteristic when it comes

to the aging of green coffee,” says Clark, who, along with

Hansen, has passed the Coffee Quality Institute’s Arabica

Grader exams, an advanced certification that underpins

their sensory evaluations. “Usually, it’s the aroma that fades.

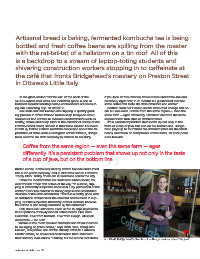

Ian Clark, Bridgehead’s director of coffee, is serious about his java.

science.carleton.ca 12