Page 516 - Geosystems An Introduction to Physical Geography 4th Canadian Edition

P. 516

480 part III The Earth–Atmosphere Interface

F cus Study 15.2 Natural Hazards Flooding in Southern Alberta in 2013

Albertans are accustomed to flooding— higher flows occur every spring as winter snow melts in the Rocky Mountains and a network of rivers drains eastward toward Hudson Bay (Geosystems Now in Chapter 9 describes this geography). In June 2013, massive flooding occurred across south- ern Alberta, causing extensive damage and hardship. Estimates of damage and recovery costs are now more than CAD

$6 billion, making it Canada’s costliest natu- ral disaster.

What were the causes of this flood- ing? What were the impacts, short-term and longer-term? What lessons were learned for the future, if any, from these events? While some lessons may appear to be simple—avoid building or living in areas known to flood—bringing about change amidst the consequences of past development is not straightforward.

Causes of the Flooding

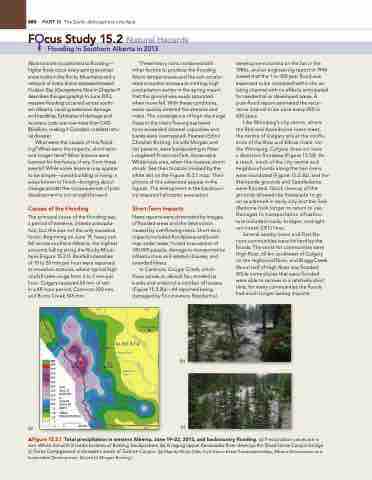

The principal cause of the flooding was a period of extreme, intense precipita- tion, but this was not the only causative factor. Beginning on June 19, heavy rain fell across southern Alberta, the highest amounts falling along the Rocky Moun- tains (Figure 15.2.1). Rainfall intensities of 10 to 20 mm per hour were reported at mountain stations, where typical high rainfall rates range from 3 to 5 mm per hour. Calgary received 68 mm of rain

in a 48-hour period, Canmore 200 mm, and Burns Creek 345 mm.

These heavy rains combined with other factors to produce the flooding. Warm temperatures and the rain acceler- ated mountain snowpack melting; high precipitation earlier in the spring meant that the ground was easily saturated when more fell. With these conditions, water quickly entered the streams and rivers. The convergence of high discharge flows in the rivers flowing eastward

soon exceeded channel capacities and banks were overtopped. Pearson Editor Christian Botting, his wife Morgan and her parents, were backpacking in Peter Lougheed Provincial Park, Kananaskis Wilderness area, when this massive storm struck. See their location marked by the white dot on the Figure 15.2.1 map. Their photos of this adventure appear in the figures. The entrapment in the backcoun- try required helicopter evacuation

Short-Term Impacts

news reports were dominated by images of flooded areas and the destruction caused by overflowing rivers. Short-term impacts included floodplains and build- ings under water, forced evacuations of 100 000 people, damage to transportation infrastructure and related closures, and stranded hikers.

In Canmore, Cougar Creek, which flows across an alluvial fan, eroded its banks and undercut a number of houses (Figure 15.2.2b)—44 reported being damaged by flood waters. Residential

(b)

(c)

development started on the fan in the 1980s, and an engineering report in 1994 stated that the 1-in-100 year flood was expected to be contained within the ex- isting channel with no effects anticipated for residential or developed areas. A post-flood report estimated the recur- rence interval to be once every 200 to 400 years.

Like Winnipeg’s city centre, where the Red and Assiniboine rivers meet, the centre of Calgary sits at the conflu- ence of the Bow and Elbow rivers. Un- like Winnipeg, Calgary does not have

a diversion floodway (Figure 15.33). As

a result, much of the city centre and neighbourhoods along the two rivers were inundated (Figure 15.2.3b), and the Stampede grounds and Saddledome were flooded. Quick cleanup of the grounds allowed the Stampede to go on as planned in early July, but the Sad- dledome took longer to return to use. Damages to transportation infrastruc- ture included roads, bridges, and light rail transit (LRT) lines.

Several nearby towns and First na- tions communities were hit hard by the floods. The worst-hit communities were High River, 60 km southwest of Calgary on the Highwood River, and Bragg Creek. About half of High River was flooded. While some places that were flooded were able to recover in a relatively short time, for many communities the floods had much longer-lasting impacts.

52o 116o 114o 112o

B.C.

Canmore Calgary

High River

A L B E RTA

Elbow River

Drumheller

MM

325

300

275

250

225

200 2013

175 June 19 150 6:00 A.M.

to

125 June 22 100 6:00 A.M. 75 (MDT)

x

Highwood River

Lethbridge

(a)

50 TOTAL

25 PRECIPITATION

1

0 0 50 KM

114 o U.S.A.

112 o

mFigure 15.2.1 Total precipitation in western Alberta, June 19–22, 2013, and backcountry flooding. (a) Precipitation values are in mm. White dot with X marks location of Botting backpackers. (b) A raging Upper Kananaskis River destroys the Dead Horse Canyon bridge. (c) Forks Campground underwater, south of Turbine Canyon. [(a) Map by Philip giles, from Storm Event Precipitation Map, Alberta Environment and Sustainable Development. (b) and (c) Morgan Botting.]

Red Deer River

Bow River

S. Saskatchewan River