Page 84 - Ming_China_Courts_and_Contacts_1400_1450 Craig lunas

P. 84

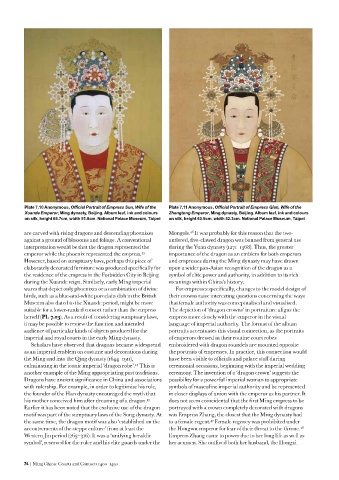

Plate 7.10 Anonymous, Official Portrait of Empress Sun, Wife of the Plate 7.11 Anonymous, Official Portrait of Empress Qian, Wife of the

Xuande Emperor, Ming dynasty, Beijing. Album leaf, ink and colours Zhengtong Emperor, Ming dynasty, Beijing. Album leaf, ink and colours

on silk, height 65.7cm, width 51.8cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei on silk, height 63.5cm, width 52.3cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei

are carved with rising dragons and descending phoenixes Mongols. It was probably for this reason that the two-

46

against a ground of blossoms and foliage. A conventional antlered, five-clawed dragon was banned from general use

interpretation would be that the dragon represented the during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). Thus, the greater

emperor while the phoenix represented the empress. importance of the dragon as an emblem for both emperors

43

However, based on sumptuary laws, perhaps this piece of and empresses during the Ming dynasty may have drawn

elaborately decorated furniture was produced specifically for upon a wider pan-Asian recognition of the dragon as a

the residence of the empress in the Forbidden City in Beijing symbol of elite power and authority, in addition to its rich

during the Xuande reign. Similarly, early Ming imperial meanings within China’s history.

wares that depict only phoenixes or a combination of divine For empresses specifically, changes to the model design of

birds, such as a blue-and-white porcelain dish in the British their crowns raise interesting questions concerning the ways

Museum also dated to the Xuande period, might be more that female authority was conceptualised and visualised.

suitable for a lower-ranked consort rather than the empress The depiction of ‘dragon crowns’ in portraiture aligns the

herself (Pl. 7.13). As a result of considering sumptuary laws, empress more closely with the emperor in the visual

it may be possible to review the function and intended language of imperial authority. The format of the album

audience of particular kinds of objects produced for the portraits accentuates this visual connection, as the portraits

imperial and royal courts in the early Ming dynasty. of emperors dressed in their routine court robes

Scholars have observed that dragons became widespread embroidered with dragon roundels are mounted opposite

as an imperial emblem on costume and decorations during the portraits of empresses. In practice, this connection would

the Ming and into the Qing dynasty (1644–1911), have been visible to officials and palace staff during

culminating in the iconic imperial ‘dragon robe’. This is ceremonial occasions, beginning with the imperial wedding

44

another example of the Ming appropriating past traditions. ceremony. The invention of a ‘dragon crown’ suggests the

Dragons have ancient significance in China and associations possibility for a powerful imperial woman to appropriate

with rulership. For example, in order to legitimise his rule, symbols of masculine imperial authority and be represented

the founder of the Han dynasty encouraged the myth that in closer displays of union with the emperor as his partner. It

his mother conceived him after dreaming of a dragon. does not seem coincidental that the first Ming empress to be

45

Earlier it has been noted that the exclusive use of the dragon portrayed with a crown completely decorated with dragons

motif was part of the sumptuary laws of the Song dynasty. At was Empress Zhang, the closest that the Ming dynasty had

the same time, the dragon motif was also ‘established on the to a female regent. Female regency was prohibited under

47

accoutrements of the steppe culture’ from at least the the Hongwu emperor for fear of their threat to the throne.

48

Western Jin period (265–316). It was a ‘unifying heraldic Empress Zhang came to power due to her long life as well as

symbol’, reserved for the ruler and his elite guards under the her acumen. She outlived both her husband, the Hongxi

74 | Ming China: Courts and Contacts 1400–1450