Page 57 - Christies Alsdorf Collection Part 1 Sept 24 2020 NYC

P. 57

establish an independent sultanate called Ma’bar; it

lasted till the founder of Vijayanagara put an end to

it and reestablished temple worship of the type that

existed under the Cholas. Early in that intervening

period, inscriptions from once famous Chola temples,

like Tiruvenkadu, speak of festivals and rituals being

re-inaugurated through generous donations from the

Pandya rulers of Madurai. While bronze workshops

would have found themselves short of work, and many

wax modellers and bronze-casters must have moved

away, a few centers clearly continued working after

Chola rule crumbled.

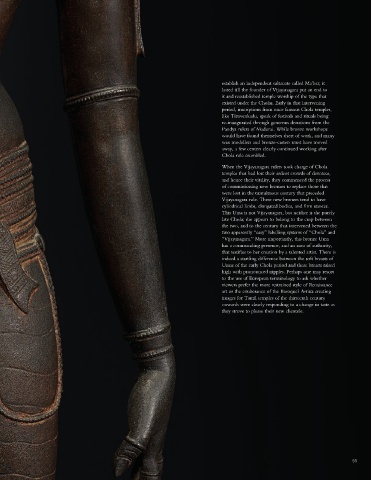

When the Vijayanagara rulers took charge of Chola

temples that had lost their ardent crowds of devotees,

and hence their vitality, they commenced the process

of commissioning new bronzes to replace those that

were lost in the tumultuous century that preceded

Vijayanagara rule. These new bronzes tend to have

cylindrical limbs, elongated bodies, and firm stances.

This Uma is not Vijayanagara, but neither is she purely

late Chola; she appears to belong to the cusp between

the two, and to the century that intervened between the

two apparently “easy” labelling systems of “Chola” and

“Vijayanagara.” More importantly, this bronze Uma

has a commanding presence, and an aura of authority,

that testifies to her creation by a talented artist. There is

indeed a startling difference between the soft breasts of

Umas of the early Chola period and these breasts raised

high with pronounced nipples. Perhaps one may resort

to the use of European terminology to ask whether

viewers prefer the more restrained style of Renaissance

art or the exuberance of the Baroque? Artists creating

images for Tamil temples of the thirteenth century

onwards were clearly responding to a change in taste as

they strove to please their new clientele.

55