Page 200 - The Arts of China, By Michael Sullivan Good Book

P. 200

conquest possible and threw them back into the desert, an empty

husk.

Politically the Yuan Dynasty may have been brief and inglo-

rious, but it is a period of special interest and importance in the

history of Chinese art—a period when men, uncertain of the pres-

ent, looked both backward and forward. Their backward-look-

ing is shown in the tendency, in painting as much as in the deco-

rative arts, to revive ancient styles, particularly those of the T'ang

Dynasty, which had been preserved in a semi-fossilised state in

North China under the alien Liao and Chin dynasties. At the same

time, the Yuan Dynasty was in several respects revolutionary, for

not only were those revived traditions given a new interpretation

but the divorce between the court and the intellectuals brought

about by the Mongol occupation instilled in the scholar class a

conviction of belonging to a self-contained elite that was not un-

dermined until the twentieth century and was to have an enor-

mous influence on painting.

In the arts and crafts, the Yii.ui Dynasty saw many innovations,

a reaction against Sung refinement and a new boldness, even gar-

ishness, in decoration. Some of these changes reflect the taste of

the Mongol conquerors themselves and of the Se-mu, the non-

Chinese peoples such as Uighurs, Tanguts, and Turks whom the

Mongols had swept up in their Drang nach Osten and established as

fief-holders and landlords in occupied China—a new and partly

Sinicised aristocracy which the dispossessed Chinese gentry, par-

ticularly in the south, looked on with a mixture of envy and con-

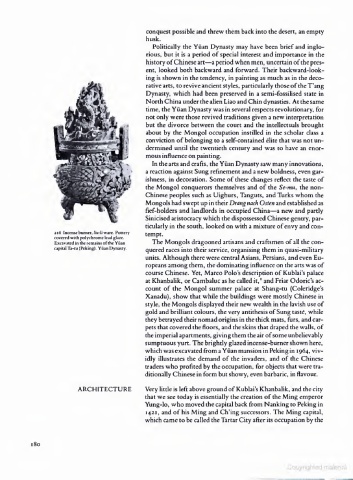

ai6 Intense burner. liu-li wire. Pottery

tempt.

covered with polychrome lead glue.

Excavated in the remains of the Yuan The Mongols dragooned artisans and craftsmen of all the con-

capital Ta-tu (Peking). Yuan Dynasty. quered races into their service, organising them in quasi-military

units. Although there were central Asians, Persians, and even Eu-

ropeans among them, the dominating influence on the arts was of

course Chinese. Yet, Marco Polo's description of Kublai's palace

1

at Khanbalik, or Cambaluc as he called it, and Friar Odoric's ac-

count of the Mongol summer palace at Shang-tu (Coleridge's

Xanadu), show that while the buildings were mostly Chinese in

style, the Mongols displayed their new wealth in the lavish use of

^old and brilliant colours, the very antithesis of Sung taste? , while

they betrayed their nomad origins in the thick mats, furs, and car-

pets that covered the floors, and the skins that draped the walls, of

the imperial apartments, giving them the air ofsome unbelievably

sumptuous yurt. The brightly glazed incense-burner shown here,

which was excavated from a Yuan mansion in Peking in 1964, viv-

idly illustrates the demand of the invaders, and of the Chinese

traders who profited by the occupation, for objects that were tra-

ditionally Chinese in form but showy, even barbaric, in flavour.

ARCHITECTURE Very little is left above ground of Kublai's Khanbalik, and the city

that we see today is essentially the creation of the Ming emperor

Yung-lo, who moved the capital back from Nanking to Peking in

1 42 1 and of his Ming and Ch'ing successors. The Ming capital,

,

which came to be called the Tartar City after its occupation by the

180