Page 201 - The Arts of China, By Michael Sullivan Good Book

P. 201

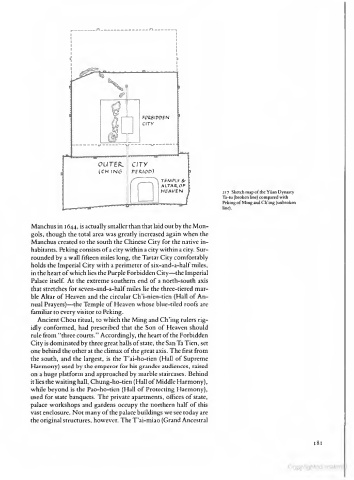

217 Sketch map of the Yuan Dynasty

Ta-tu (broken line) compared with

Peking ol" Ming and Ch'ing (unbroken

line).

Manchus in 1644, is actually smaller than that laid out by the Mon-

gols, though the total area was greatly increased again when the

Manchus created to the south the Chinese City for the native in-

habitants. Peking consists of a city within a city within a city. Sur-

rounded by a wall fifteen miles long, the Tartar City comfortably

holds the Imperial City with a perimeter of six-and-a-half miles,

in the heart of which lies the Purple Forbidden City—the Imperial

Palace itself. At the extreme southern end of a north-south axis

that stretches for seven-and-a-half miles lie the three-tiered mar-

ble Altar of Heaven and the circular Ch'i-nien-tien (Hall of An-

nual Prayers)—the Temple of Heaven whose blue-tiled roofs are

familiar to every visitor to Peking.

Ancient Chou ritual, to which the Ming and Ch'ing rulers rig-

idly conformed, had prescribed that the Son of Heaven should

rule from "three courts." Accordingly, the heart of the Forbidden

City is dominated by three great halls of state, the San Ta Tien, set

one behind the other at the climax of the great axis. The first from

the south, and the largest, is the T'ai-ho-tien (Hall of Supreme

Harmony) used by the emperor for his grander audiences, raised

on a huge platform and approached by marble staircases. Behind

it lies the waiting hall, Chung-ho-tien (Hall of Middle Harmony),

while beyond is the Pao-ho-tien (Hall of Protecting Harmony),

used for state banquets. The private apartments, offices of state,

palace workshops and gardens occupy the northern half of this

vast enclosure. Not many of the palace buildings we see today are

the original structures, however. The T'ai-miao (Grand Ancestral