Page 203 - The Arts of China, By Michael Sullivan Good Book

P. 203

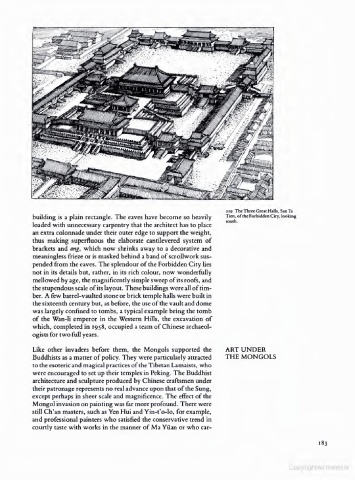

210 The Three Great Halls. San Ta

building is a plain rectangle. The eaves have become so heavily Tien, of the Forbidden City, looking

south.

loaded with unnecessary carpentry that the architect has to place

an extra colonnade under their outer edge to support the weight,

thus making superfluous the elaborate cantilcvcrcd system of

brackets and ang, which now shrinks away to a decorative and

meaningless frieze or is masked behind a band of scrollwork sus-

pended from the eaves. The splendour of the Forbidden City lies

not in its details but, rather, in its rich colour, now wonderfully

mellowed by age, the magnificently simple sweep of its roofs, and

the stupendous scale of its layout. These buildings were all of tim-

ber. A few barrel-vaulted stone or brick temple halls were built in

the sixteenth century but, as before, the use of the vault and dome

was largely confined to tombs, a typical example being the tomb

of the Wan-li emperor in the Western Hills, the excavation of

which, completed in 1958, occupied a team of Chinese archaeol-

ogists for two full years.

Like other invaders before them, the Mongols supported the ART UNDER

THE MONGOLS

Buddhists as a matter of policy. They were particularly attracted

to the esoteric and magical practices of the Tibetan Lamaists, who

were encouraged to set up their temples in Peking. The Buddhist

architecture and sculpture produced by Chinese craftsmen under

their patronage represents no real advance upon that of the Sung,

except perhaps in sheer scale and magnificence. The effect of the

Mongol invasion on painting was far more profound. There were

still Ch'an masters, such as Yen Hui and Yin-t'o-lo, for example,

and professional painters who satisfied the conservative trend in

courtly taste with works in the manner of Ma Yuan or who car-