Page 276 - The colours of each piece: production and consumption of Chinese enamelled porcelain, c.1728-c.1780

P. 276

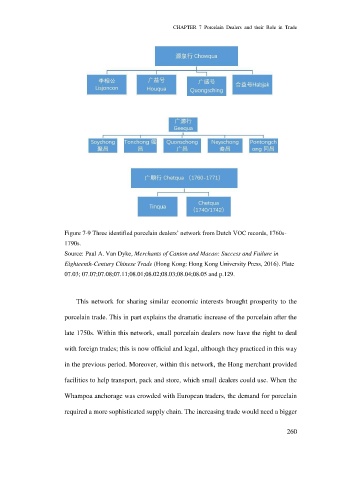

CHAPTER 7 Porcelain Dealers and their Role in Trade

Figure 7-9 Three identified porcelain dealers’ network from Dutch VOC records, 1760s-

1790s.

Source: Paul A. Van Dyke, Merchants of Canton and Macao: Success and Failure in

Eighteenth-Century Chinese Trade (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2016). Plate

07.03; 07.07;07.08;07.11;08.01;08.02;08.03;08.04;08.05 and p.129.

This network for sharing similar economic interests brought prosperity to the

porcelain trade. This in part explains the dramatic increase of the porcelain after the

late 1750s. Within this network, small porcelain dealers now have the right to deal

with foreign trades; this is now official and legal, although they practiced in this way

in the previous period. Moreover, within this network, the Hong merchant provided

facilities to help transport, pack and store, which small dealers could use. When the

Whampoa anchorage was crowded with European traders, the demand for porcelain

required a more sophisticated supply chain. The increasing trade would need a bigger

260