Page 31 - Metropolitan Museum Collection September 2016

P. 31

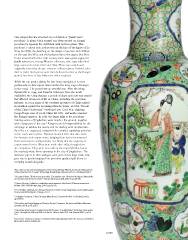

One subject that has attracted a lot of debate is “famille noire”

porcelain.7 A glossy black enamel was often created on Kangxi

porcelain by layering the dull black with lustrous green. This

produced a colour such as that seen on the hair of the fgure of Lu

Xing (lot 878), the detailing on the design of women and children

on the vase (lot 881), and the backgrounds to the teapot (lot 882).

In the second half of the 19th century there was a great vogue for

famille noire pieces among Western collectors, who especially liked

large vases such as lots 1002 and 1004. These two vessels were

originally owned by the pre-eminent collector James Garland, who

died in 1902. Such pieces were then believed to date to the Kangxi

period, but were in fact fairly new when acquired.

While we can posit a dating for late Qing examples, it is more

problematic to date export wares within the long reign of Kangxi

(1662-1722). The period was an eventful one. After the Ming

dynasty fell in 1644, and Manchu tribesmen from the north

established the Qing dynasty, a period of chaos and civil war ensued

that affected all aspects of life in China, including the porcelain

industry. In 1674 many of the southern provinces of China united

in rebellion against the incoming Manchu rulers, and this “Revolt

of the Three Feudatories” developed into Civil War. Fighting

ravaged large areas of south China till 1681, and nearly unseated

the Kangxi emperor. In 1674 the larger kilns at the porcelain-

making centre of Jingdezhen were razed to the ground, together

with a large part of the city.8 Kangxi took full responsibility for the

campaign to subdue the revolt, and for dealing with its aftermath.

By 1683 a re-organised, industrial kiln complex supplying porcelain

to the court was in place. Business boomed after that date, both

for domestic and export wares. Judging from items documented

from such sources as shipwrecks, it is likely that the majority of

export wares for the West were made after 1683, though there

are exceptions. They were not made at the imperial kilns, but at

the myriad private frms operating in the city of Jingdezhen. The

attractive pieces in this catalogue were part of that huge trade, that

gave rise to goods ranging from premium quality right down to

everyday household grade.

1 For a discussion of terminology, Rose Kerr (ed.) and Nigel Wood, Science & Civilisation in

China, Volume V:12, Ceramic Technology (Cambridge University Press, 2004), pp.634-5.

2 Suzanne Kluver, “Boek versus porselein. Een analyse van ‘Histoire Artistique, Industrielle

et Commerciale de la Porcelain’”, Vormen uit Vuur, no.218, 2012-3, pp.29-35.

3 Stacey Pierson, Collectors, collections and museums : the feld of Chinese ceramics in

Britain, 1560-1960 (Peter Lang, 2007), pp.62-65.

4 Eva Ströber, Symbols on Chinese Porcelain, 10 000 Times Happiness, Keramiekmuseum

Princessehof (Stuttgart, 2011), pp.74-79.

5 Schuyler Camman, “Some Strange Ming Bests”, Oriental Art NS, 2:3 (Oxford, 1956),

pp.94-102.

6 Rose Kerr and Luisa Mengoni, Chinese Export Ceramics, Victoria and Albert Museum

(London, 2011), p.33, pl.33.

7 A good general survey is Linda Rosenfeld Pomper, “Famille Noire Porcelains: Tracing the

Taste Through the 18th and 19th Centuries”, Arts of Asia, 43:4, July-August 2013, pp.115-

125.

8 Rose Kerr, Chinese Ceramics. Porcelain of the Qing Dynasty 1644-1911, Victoria and Albert

Museum (London, 1986), p.16.

Lot 881